Thursday, October 26

Single Screen Blues

I suspect this post can be filed under the category of "too little, too late", but I've finally found a free moment to mention something I've been meaning to here for a while now.

The Roxie Cinema is among the contenders in a contest called Partners in Preservation, set up to determine how to distribute funds to help restore and preserve historic sites in the Frisco Bay Area. Anyone, no matter their location, is encouraged to set up an account and vote once a day, every day until October 31st. I hope everyone who reads this will do just that.

The Roxie Cinema is among the contenders in a contest called Partners in Preservation, set up to determine how to distribute funds to help restore and preserve historic sites in the Frisco Bay Area. Anyone, no matter their location, is encouraged to set up an account and vote once a day, every day until October 31st. I hope everyone who reads this will do just that.

On the first day I learned about the contest, the Roxie was in first place, but since then it's steadily slipped down and is now out of the top ten (which I understand is where the theatre needs to be if it is to receive some of the funds.) I admit I haven't remembered to vote every day, and I even voted for another project once or twice while the Roxie was still at the top of the list, thinking that the independent cinema lovers who turned out initially would be a strong enough contingent to ensure its high placement throughout the polling.

An interesting aspect of the poll is that as you vote you can select a reason why you made your particular choice. Voters for the Roxie have tended to choose it because "it contributes to the vitality of the Bay Area" (as of now, 41%) or because "Saving it will improve the community" (25%) more often than because "it has historic or architectural significance" (20%). 20% is one of the lowest ratios in the latter category for any of the projects in the poll, and I suspect it's indicative of why the cinema has not ranked higher after that initial push. It's true that the building is not as striking or ornate a structure as, say, Oakland's shuttered Fox Theatre (currently holding at number four in the poll), but I for one think the Roxie, as Frisco's oldest theatre still in operation, is extremely historically and architecturally significant.

The Roxie and the 4-Star (which was twinned, non-identically, in 1996) are the only currently operating movie theatres in Frisco built specifically to show movies from what one might call the "pre-epic" era of cinema. Films were made for twenty years before the medium "came of age" as something for everyone up to and including the President of the United States, not to mention the NAACP, to take seriously, when The Birth of a Nation was released. Italian extravaganzas such as Cabiria had been imported here before, but the The Clansman (as it was originally called) was three hours long, used the most modern cinematic techniques of its day, and was controversial, to put it mildly. Incendiary may be a better word. These factors helped make it more than just a "blockbuster" film but a phenomenon that truly outlasted its moment. By March 8, 1915, the second of at least fourteen weeks at the long demolished O'Farrell Street Alcazar Theatre (which usually hosted theatre and opera at the time but made an exception for this film) it was already being advertised as "the World's Most Famous Motion Picture". To this day it's surely the most well-known film title of the silent era.

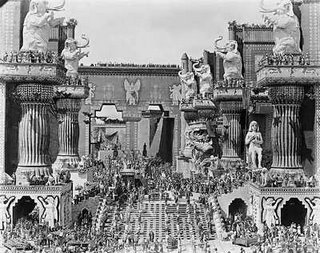

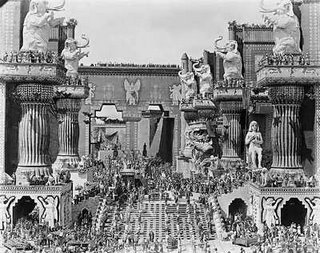

Of course the biggest cultural event in Frisco in 1915 wasn't a film but a fair: the Panama Pacific International Exposition which opened shortly before the Clansman did at the Alcazar, but outlasted the film's run there, continuing nearly all year. Stuart Klawans opens his book Film Follies with an appealing hypothesis that D.W. Griffith used the fair's architecture, a remnant of which still exists as the Palace of Fine Arts, as part of the inspiration for the gargantuan scale of Intolerance, his 1916 rejoinder to critics trying to censor the Birth of a Nation (Frisco's Board of Supervisors were among those who attempted this at the time). Intolerance was not the box office hit the previous feature was, but as Klawans points out, it wasn't the financial disaster it's been made out to be either, and it helped to inspire a wave of lavish historical epics. Interestingly, at around the same time a new type of movie theatre was emerging on the scene: the movie palace, grand and ornate, and designed to attract upscale customers to motion pictures.

Of course the biggest cultural event in Frisco in 1915 wasn't a film but a fair: the Panama Pacific International Exposition which opened shortly before the Clansman did at the Alcazar, but outlasted the film's run there, continuing nearly all year. Stuart Klawans opens his book Film Follies with an appealing hypothesis that D.W. Griffith used the fair's architecture, a remnant of which still exists as the Palace of Fine Arts, as part of the inspiration for the gargantuan scale of Intolerance, his 1916 rejoinder to critics trying to censor the Birth of a Nation (Frisco's Board of Supervisors were among those who attempted this at the time). Intolerance was not the box office hit the previous feature was, but as Klawans points out, it wasn't the financial disaster it's been made out to be either, and it helped to inspire a wave of lavish historical epics. Interestingly, at around the same time a new type of movie theatre was emerging on the scene: the movie palace, grand and ornate, and designed to attract upscale customers to motion pictures.

Up until a few weeks ago there were two such theatres in Frisco still showing films and essentially architecturally unchanged (that is, still operating as single-screen theatres), though both were built to be neighborhood theatres, not quite as grand and ornate as a downtown theatre like the Granada. One is the 1922-built Castro, and the other was Union Street's Metro, originally opened as the Metropolitan in 1924, and renamed in 1941. Sadly, though not surprisingly, it finally closed down last month. I can't pretend that I was a regular customer myself; the fact that it was a great, recently refurbished space with a staff that took pride in its high-quality presentations, and that it even boasted the largest screen in town once the Coronet shut its doors for good in early 2005, couldn't make up for the unappealing selection of Hollywood movies that inevitably dominated its screen in recent years. The last film I saw there was the Village, more than two years ago. The SF Neighborhood Theatre Foundation has started a letter-writing campaign to try to keep the space a theatre, and I would think the Film Society might be invested in such a project too. The Metro was the site of its International Film Festival during its earliest years, including the very first festival back in 1957. (A year after the success of its first event, an Italian Film Festival including La Strada at the Alexandria. Fifty years later, the society still has an annual focus on Italian cinema, and this year's edition, November 12-19, will include a three-film tribute to Marco Bellocchio at the Embarcadero).

But the Roxie still survives intact as a single screen theatre, with the Little Roxie adjunct two doors down helping to keep it viable in a marketplace where flexible booking is a distinct advantage. The upcoming schedule is filled with documentaries, and the theatre rarely plays the sorts of overbudgeted monstrosities straining too hard to lend credibility to the cinematic medium that the likes of The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance still serve as models for. Yet the Roxie isn't above (or is it beneath) putting a certain kind of epic on its screen once in a while, and will do so November 12 when the South Asian Film Festival brings the four-hour Hindi action classic Sholay there.

And the Castro still operates as a full-time single-screener for independent and classic films. More than a year ago I wrote about my ambivalence attending the venue in the wake of its owners' unexplained firing of longtime programmer Anita Monga, but I have to admit it's the kind of ambivalence that seems to fade somewhat with 1) the passage of time and 2) continuously improving programming choices. With the Balboa's turn away from repertory programming other than occasional events like the upcoming Louise Brooks centennial celebration, and Noir City's announced return to the Castro this January, I don't think there's much point for Frisco cinephiles to fight the urge to go the movie palace anymore. Even the Film Arts Foundation, which lists Monga among its board members, is returning the venue for its 30th anniversary November 14th. The next Castro calendar is not available quite yet, but it looks to be the best since her departure. It's a site for the Latino Film Festival November 3-5 (the festival continues at other venues through the 19th). Billy Wilder's best film Ace in the Hole plays there November 7th and a Douglas Sirk double-bill appears two days later. November 10 brings a MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS breakdancing triple-bill (Breakin', Beat Street and, uh, Cool As Ice). A Tennessee Williams film series including films directed by Elia Kazan, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, and Joseph Losey runs November 12-15. Grey Gardens plays with the follow-up the Beales of Grey Gardens November 21-22. And November concludes with four days of Japanese New Waver Hiroshi Teshigahara's best films: the Face of Another (on the 27th), Pitfall (the 28th), Woman in the Dunes (29th) and Antonio Gaudi (30th). And that's all just next month! I'm not even sure just what's in store for December, except that it starts out strong with a Silent Film Festival presentation of the original Cecil B. DeMille-produced Chicago and a set of Silly Symphonies including the groundbreaking, gleefully macabre the Skeleton Dance on the 2nd.

And the Castro still operates as a full-time single-screener for independent and classic films. More than a year ago I wrote about my ambivalence attending the venue in the wake of its owners' unexplained firing of longtime programmer Anita Monga, but I have to admit it's the kind of ambivalence that seems to fade somewhat with 1) the passage of time and 2) continuously improving programming choices. With the Balboa's turn away from repertory programming other than occasional events like the upcoming Louise Brooks centennial celebration, and Noir City's announced return to the Castro this January, I don't think there's much point for Frisco cinephiles to fight the urge to go the movie palace anymore. Even the Film Arts Foundation, which lists Monga among its board members, is returning the venue for its 30th anniversary November 14th. The next Castro calendar is not available quite yet, but it looks to be the best since her departure. It's a site for the Latino Film Festival November 3-5 (the festival continues at other venues through the 19th). Billy Wilder's best film Ace in the Hole plays there November 7th and a Douglas Sirk double-bill appears two days later. November 10 brings a MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS breakdancing triple-bill (Breakin', Beat Street and, uh, Cool As Ice). A Tennessee Williams film series including films directed by Elia Kazan, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, and Joseph Losey runs November 12-15. Grey Gardens plays with the follow-up the Beales of Grey Gardens November 21-22. And November concludes with four days of Japanese New Waver Hiroshi Teshigahara's best films: the Face of Another (on the 27th), Pitfall (the 28th), Woman in the Dunes (29th) and Antonio Gaudi (30th). And that's all just next month! I'm not even sure just what's in store for December, except that it starts out strong with a Silent Film Festival presentation of the original Cecil B. DeMille-produced Chicago and a set of Silly Symphonies including the groundbreaking, gleefully macabre the Skeleton Dance on the 2nd.

As for the Birth of a Nation, it will have a rare screening with a recorded score at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum on November 12, a day devoted to Griffith films and part of a weekend of silent films by notable directors (also to include Dreyer, Feyder, Lang & Hitchcock).

The Roxie Cinema is among the contenders in a contest called Partners in Preservation, set up to determine how to distribute funds to help restore and preserve historic sites in the Frisco Bay Area. Anyone, no matter their location, is encouraged to set up an account and vote once a day, every day until October 31st. I hope everyone who reads this will do just that.

The Roxie Cinema is among the contenders in a contest called Partners in Preservation, set up to determine how to distribute funds to help restore and preserve historic sites in the Frisco Bay Area. Anyone, no matter their location, is encouraged to set up an account and vote once a day, every day until October 31st. I hope everyone who reads this will do just that.On the first day I learned about the contest, the Roxie was in first place, but since then it's steadily slipped down and is now out of the top ten (which I understand is where the theatre needs to be if it is to receive some of the funds.) I admit I haven't remembered to vote every day, and I even voted for another project once or twice while the Roxie was still at the top of the list, thinking that the independent cinema lovers who turned out initially would be a strong enough contingent to ensure its high placement throughout the polling.

An interesting aspect of the poll is that as you vote you can select a reason why you made your particular choice. Voters for the Roxie have tended to choose it because "it contributes to the vitality of the Bay Area" (as of now, 41%) or because "Saving it will improve the community" (25%) more often than because "it has historic or architectural significance" (20%). 20% is one of the lowest ratios in the latter category for any of the projects in the poll, and I suspect it's indicative of why the cinema has not ranked higher after that initial push. It's true that the building is not as striking or ornate a structure as, say, Oakland's shuttered Fox Theatre (currently holding at number four in the poll), but I for one think the Roxie, as Frisco's oldest theatre still in operation, is extremely historically and architecturally significant.

The Roxie and the 4-Star (which was twinned, non-identically, in 1996) are the only currently operating movie theatres in Frisco built specifically to show movies from what one might call the "pre-epic" era of cinema. Films were made for twenty years before the medium "came of age" as something for everyone up to and including the President of the United States, not to mention the NAACP, to take seriously, when The Birth of a Nation was released. Italian extravaganzas such as Cabiria had been imported here before, but the The Clansman (as it was originally called) was three hours long, used the most modern cinematic techniques of its day, and was controversial, to put it mildly. Incendiary may be a better word. These factors helped make it more than just a "blockbuster" film but a phenomenon that truly outlasted its moment. By March 8, 1915, the second of at least fourteen weeks at the long demolished O'Farrell Street Alcazar Theatre (which usually hosted theatre and opera at the time but made an exception for this film) it was already being advertised as "the World's Most Famous Motion Picture". To this day it's surely the most well-known film title of the silent era.

Of course the biggest cultural event in Frisco in 1915 wasn't a film but a fair: the Panama Pacific International Exposition which opened shortly before the Clansman did at the Alcazar, but outlasted the film's run there, continuing nearly all year. Stuart Klawans opens his book Film Follies with an appealing hypothesis that D.W. Griffith used the fair's architecture, a remnant of which still exists as the Palace of Fine Arts, as part of the inspiration for the gargantuan scale of Intolerance, his 1916 rejoinder to critics trying to censor the Birth of a Nation (Frisco's Board of Supervisors were among those who attempted this at the time). Intolerance was not the box office hit the previous feature was, but as Klawans points out, it wasn't the financial disaster it's been made out to be either, and it helped to inspire a wave of lavish historical epics. Interestingly, at around the same time a new type of movie theatre was emerging on the scene: the movie palace, grand and ornate, and designed to attract upscale customers to motion pictures.

Of course the biggest cultural event in Frisco in 1915 wasn't a film but a fair: the Panama Pacific International Exposition which opened shortly before the Clansman did at the Alcazar, but outlasted the film's run there, continuing nearly all year. Stuart Klawans opens his book Film Follies with an appealing hypothesis that D.W. Griffith used the fair's architecture, a remnant of which still exists as the Palace of Fine Arts, as part of the inspiration for the gargantuan scale of Intolerance, his 1916 rejoinder to critics trying to censor the Birth of a Nation (Frisco's Board of Supervisors were among those who attempted this at the time). Intolerance was not the box office hit the previous feature was, but as Klawans points out, it wasn't the financial disaster it's been made out to be either, and it helped to inspire a wave of lavish historical epics. Interestingly, at around the same time a new type of movie theatre was emerging on the scene: the movie palace, grand and ornate, and designed to attract upscale customers to motion pictures.Up until a few weeks ago there were two such theatres in Frisco still showing films and essentially architecturally unchanged (that is, still operating as single-screen theatres), though both were built to be neighborhood theatres, not quite as grand and ornate as a downtown theatre like the Granada. One is the 1922-built Castro, and the other was Union Street's Metro, originally opened as the Metropolitan in 1924, and renamed in 1941. Sadly, though not surprisingly, it finally closed down last month. I can't pretend that I was a regular customer myself; the fact that it was a great, recently refurbished space with a staff that took pride in its high-quality presentations, and that it even boasted the largest screen in town once the Coronet shut its doors for good in early 2005, couldn't make up for the unappealing selection of Hollywood movies that inevitably dominated its screen in recent years. The last film I saw there was the Village, more than two years ago. The SF Neighborhood Theatre Foundation has started a letter-writing campaign to try to keep the space a theatre, and I would think the Film Society might be invested in such a project too. The Metro was the site of its International Film Festival during its earliest years, including the very first festival back in 1957. (A year after the success of its first event, an Italian Film Festival including La Strada at the Alexandria. Fifty years later, the society still has an annual focus on Italian cinema, and this year's edition, November 12-19, will include a three-film tribute to Marco Bellocchio at the Embarcadero).

But the Roxie still survives intact as a single screen theatre, with the Little Roxie adjunct two doors down helping to keep it viable in a marketplace where flexible booking is a distinct advantage. The upcoming schedule is filled with documentaries, and the theatre rarely plays the sorts of overbudgeted monstrosities straining too hard to lend credibility to the cinematic medium that the likes of The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance still serve as models for. Yet the Roxie isn't above (or is it beneath) putting a certain kind of epic on its screen once in a while, and will do so November 12 when the South Asian Film Festival brings the four-hour Hindi action classic Sholay there.

And the Castro still operates as a full-time single-screener for independent and classic films. More than a year ago I wrote about my ambivalence attending the venue in the wake of its owners' unexplained firing of longtime programmer Anita Monga, but I have to admit it's the kind of ambivalence that seems to fade somewhat with 1) the passage of time and 2) continuously improving programming choices. With the Balboa's turn away from repertory programming other than occasional events like the upcoming Louise Brooks centennial celebration, and Noir City's announced return to the Castro this January, I don't think there's much point for Frisco cinephiles to fight the urge to go the movie palace anymore. Even the Film Arts Foundation, which lists Monga among its board members, is returning the venue for its 30th anniversary November 14th. The next Castro calendar is not available quite yet, but it looks to be the best since her departure. It's a site for the Latino Film Festival November 3-5 (the festival continues at other venues through the 19th). Billy Wilder's best film Ace in the Hole plays there November 7th and a Douglas Sirk double-bill appears two days later. November 10 brings a MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS breakdancing triple-bill (Breakin', Beat Street and, uh, Cool As Ice). A Tennessee Williams film series including films directed by Elia Kazan, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, and Joseph Losey runs November 12-15. Grey Gardens plays with the follow-up the Beales of Grey Gardens November 21-22. And November concludes with four days of Japanese New Waver Hiroshi Teshigahara's best films: the Face of Another (on the 27th), Pitfall (the 28th), Woman in the Dunes (29th) and Antonio Gaudi (30th). And that's all just next month! I'm not even sure just what's in store for December, except that it starts out strong with a Silent Film Festival presentation of the original Cecil B. DeMille-produced Chicago and a set of Silly Symphonies including the groundbreaking, gleefully macabre the Skeleton Dance on the 2nd.

And the Castro still operates as a full-time single-screener for independent and classic films. More than a year ago I wrote about my ambivalence attending the venue in the wake of its owners' unexplained firing of longtime programmer Anita Monga, but I have to admit it's the kind of ambivalence that seems to fade somewhat with 1) the passage of time and 2) continuously improving programming choices. With the Balboa's turn away from repertory programming other than occasional events like the upcoming Louise Brooks centennial celebration, and Noir City's announced return to the Castro this January, I don't think there's much point for Frisco cinephiles to fight the urge to go the movie palace anymore. Even the Film Arts Foundation, which lists Monga among its board members, is returning the venue for its 30th anniversary November 14th. The next Castro calendar is not available quite yet, but it looks to be the best since her departure. It's a site for the Latino Film Festival November 3-5 (the festival continues at other venues through the 19th). Billy Wilder's best film Ace in the Hole plays there November 7th and a Douglas Sirk double-bill appears two days later. November 10 brings a MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS breakdancing triple-bill (Breakin', Beat Street and, uh, Cool As Ice). A Tennessee Williams film series including films directed by Elia Kazan, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, and Joseph Losey runs November 12-15. Grey Gardens plays with the follow-up the Beales of Grey Gardens November 21-22. And November concludes with four days of Japanese New Waver Hiroshi Teshigahara's best films: the Face of Another (on the 27th), Pitfall (the 28th), Woman in the Dunes (29th) and Antonio Gaudi (30th). And that's all just next month! I'm not even sure just what's in store for December, except that it starts out strong with a Silent Film Festival presentation of the original Cecil B. DeMille-produced Chicago and a set of Silly Symphonies including the groundbreaking, gleefully macabre the Skeleton Dance on the 2nd.As for the Birth of a Nation, it will have a rare screening with a recorded score at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum on November 12, a day devoted to Griffith films and part of a weekend of silent films by notable directors (also to include Dreyer, Feyder, Lang & Hitchcock).

Friday, October 20

Adam Hartzell on Ali Kazimi

The Pacific Film Archive has its new calendar up. It's unsurprisingly packed with must-sees. As disappointing as it's been to learn that my neighborhood theatre the Balboa would in fact not be a venue for a Janus Films tribute this fall, knowing that the PFA is tackling two such series, one largely Europe-focused and the other Japanese is something of a balm. Just as enticing are the Jacques Rivette series, a set of Beat-era films, and a fascinating series guest-programmed by Akram Zaatari. And more. It almost makes me want to move to Berkeley.

The Pacific Film Archive has its new calendar up. It's unsurprisingly packed with must-sees. As disappointing as it's been to learn that my neighborhood theatre the Balboa would in fact not be a venue for a Janus Films tribute this fall, knowing that the PFA is tackling two such series, one largely Europe-focused and the other Japanese is something of a balm. Just as enticing are the Jacques Rivette series, a set of Beat-era films, and a fascinating series guest-programmed by Akram Zaatari. And more. It almost makes me want to move to Berkeley.Adam Hartzell, who is currently in Busan, South Korea enjoying what is widely thought of as the best international film festival in Asia, the PIFF (and yes I'm extremely jealous that he gets to see stuff like Syndromes and a Century and Woman on the Beach and I don't), has been kind enough to let me publish a pair of reports on series devoted to documentarian artists-in-residence at the PFA. Here is a third one, on last month's resident Ali Kazimi. Adam:

Thanks to funding by a grant from the Consortium for the Arts at UC Berkeley and presentation support by EKTA and 3rd I: South Asian Films, Indian-Canadian director Ali Kazimi came to town again, enabling Bay Area eyes their third chance to see Continuous Journey, a film which challenges the "liberal" history that is larger Canada's. In 1914, 376 citizens of the British Empire from British India sailed to Vancouver Bay on the Kamagata Maru. They should have been allowed entry onto the shores of Vancouver Bay since they were subjects of the King of England. But this was a year where Canadian pubs were rowdy with the chants of "White Canada Forever" and these subjects were denied entry. The hidden history that Continuous Journey reveals left an impact on me. Which is why I made the trek under the bay to the Pacific Film Archives to catch what I could of the rest of Kazimi's works. The other films and shorts screened in the weekend retrospective (September 14-16, 2006) demonstrated that Kazimi was not done teaching me.

Born and raised in Delhi, India Kazimi didn't grow up around "film", meaning the images shown on screens, but did grow up around film, that is, the material that enables those images to flicker on those very screens. His father worked for Kodak and the smells of chemicals and film stock still stimulate memory nodes of childhood in Kazimi as the smell of pine lumber brings back memories for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) Indian-Canadian reporter in his documentary on Indian immigration in Canada. Although it makes sense that he would become a freelance photographer, Kazimi does not resign his path to that of a fated trajectory. He is well aware of all the work and risk required to bring him to where he is today. He taught himself photography from what was lying around his house rather than through mentored instruction. And his shift to film presents similar agency. While working on a marketing campaign in rural India to sell soft drinks, Kazimi asked his superior "Why?" That is, why were they selling hyper-sugar-ed drinks in an impoverished area where basic nutrients are commonly unavailable? A valid argument outside of standard business protocol. The "Why?" question was then thrown back at him, as in, 'Why are you here then?' Kazimi actively listened to this echo and changed the focus of his artistic lens towards film and radio projects. Kazimi would eventually realize that for him to make the films he really wanted to make, he had to leave India for Canada, where he found greater access to funding, intellectual freedom, and distribution, (although not a perfect scenario, as I will note later.)

'Who is speaking for whom?' is a constant question for Kazimi throughout his work. Although acknowledging the point can not be made without over-generalizing, he stated that upon coming to Canada he found the portrayals of people from the Indian subcontinent awash in stereotypes and other clichés and wanted to change that. Much of his work through the funding of the CBC and the National Film Board of Canada has enabled an opportunity to address these poorly painted pictures of a vast, diverse community. "Passage from India" was his contribution to a wider CBC series on the experiences of various Canadian immigrant communities. It follows a CBC newscaster who is the third descendent of Bagga Singh, one of the earliest Indian immigrants to Canada. The piece notes the Indian presence in the logging industry, placing Indians clearly within the iconic landscape that is Canada's symbol of herself.

And it is that landscape that follows Kazimi. Through the assistance of an interviewer's persistence to know whence Kazimi's ideas came, Kazimi realized he was searching for the answer to another question: How do people like him, relatively recent arrivals, fit into the Canadian landscape? He seems to have realized the answers to that question by emphasizing that all Indian immigrants to Canada will not "fit" the same way. In a piece about arranged marriages in the Indian-Canadian community entitled Some Kind of Arrangement, Kazimi follows three different Indian-Canadians from three different religious traditions: one Hindu, one Muslim, and one Sikh. Each has returned to the tradition of arranged marriages for a different reason. One subject comes to the arrangement quite quickly, at least in terms of physical presence. She only saw her future husband twice before their wedding week. Another subject comes from Marxist parents who met through falling in love rather than through arrangement. And another one comes from an ambiguous claim for "traditional" Indian values. Well-crafted and paced, this documentary allows for the emergence of the natural contradictions in our lives without appearing judgmental. The young Sikh-Canadian who longs for "traditional" values isn't able to explain in great depth what she means by "traditional". But when her arranged date demands he drive her car, she takes serious offence. These aren't moments to satisfy our sadistic chastising desires, but moments we can relate to, aware of our own trails as we try to negotiate romantic relationships that emerge through our familial, social, business, and computer networks. We might think we want one thing until the intersubjectivity with others causes us to adjust our categorization of our values so that they better explain ourselves to ourselves, let alone to others.Kazimi said he was reluctant to do Some Kind of Arrangement, and not just because such would require him to go against the informal pledge made amongst his fist-raised, filmmaking buddies to 'Never Make a Wedding Video!!!' He was primarily reluctant because he had deep-seated prejudices against the practice. But he presents three vastly divergent personal stories surrounding an issue that is most often lazily described as an archaic illegitimate practice. It was a woman I dated in college who pushed me beyond the lazy perspective I used to have on arranged marriages. She explained to me why she wasn't averse to taking her parents up on their offer to arrange a marriage for her within the Korean Seventh Day Adventist community. She had final veto on who would be eventually chosen and she trusted her parents enough to find someone in tune with what she wanted as a modern American woman. Although still not an arrangement I would choose, as notes one of the friends attending the arranged Hindi wedding in the documentary, 'Don't our friends and family arrange parties or other get togethers in hopes of assisting in their child's romantic union?' Yes, and the marriage-proposal newspapers of the Indian community have similarities to the Evangelical Christian ruse of eHarmony or the more democratic forum of Yahoo! Personals. So continues the paradox that it is amongst our differences that we find our similarities.

But there are certain practices to arranged marriages, such as the speed with which some happen and the unequal power dynamics often involved, that allow arranged marriages to be vulnerable to certain dangers. The trust required in the process can be more easily exploited by less than trustworthy folk. And it is this "darker side" of such marriages that Kazimi was equally reluctant to explore in Runaway Grooms. This documentary for the CBC brought Kazimi back to India to interview women who have been abandoned by their arranged husbands after these husbands and their complicit family members extorted as much dowry money and jewels from the arranged bride as they could. This abandonment is enabled by the men having Non-Resident-Indian (NRI) status that allows them to evade legal prosecution and direct moral consequence. Left in India with sympathetic biological families, cultural traditions make it difficult for these abandoned brides to remarry, to work, and to interact socially, while international political options benefiting their deadbeat husbands allows the husbands to petition for divorces once they've milked all the money they could out of their arranged spouses. Kazimi utilizes regular documentary tactics of narration and expert commentary to explain the tradition of the dowry and the options available, and not available, to these women and men and how economics and politics truly benefit the men. Although I'm sure Kazimi would still refuse to do a wedding video, the archival footage of both arranged marriages in this short allow for a tense, suspenseful structure of the narrative as we sit with the unease of the ceremony and speculate about the unease on the face of the soon-to-runaway first groom and the disgusting disinterest on the face of the second.

Kazimi uses the documentary form to demonstrate that these are not just personal choices and cultural practices, they are political in that the legal structure acts as an accomplice to the crimes of the 'runaway grooms'. Feminists are often portrayed falsely as 'man-haters' when they dare to shed light on these patriarchal elephants in our rooms. Kazimi's direction helps limit the justification (when there ever is one) for such weak reactive arguments against Feminisms by introducing us to some of the people who are seeking to remove these patriarchal parameters, some of whom are men. And returning to Kazimi's concern about how Indians are portrayed in the media, coupling Some Kind of Arrangement with Runaway Grooms at a single screening in this retrospective allows for a fuller picture of Indian cultures, emphasizing the plural. Kazimi demonstrates through both these pieces that he strives to show the complexity of the Indian diaspora, which includes the cultural practices that need to be supported and maintained, revisited and revised, or condemned and abolished.Kazimi carries this to portrayals of other cultures as well. His thesis film was a test of patience, patience with all the obstacles that come up when making a film, patience with the subject, and patience with himself. While doing research to find a topic for his thesis film, Kazimi came across the work of Iroquois photographer Jeffrey Thomas. Little did he know that a 12-year process was about to begin. The film, Shooting Indians, took that long to finish because Thomas had abandoned the project well before completion. (In the interim, Kazimi would go off to India to film Narmada: A Valley Rises about the activists who tried to stop the relocation of millions of Indian villagers to make way for the Narmada Valley Dam.) Kazimi was only able to return to the project when a chance meeting with Thomas's son enabled Kazimi and Thomas to reconnect. Thomas let Kazimi know that it was his own self-doubt that caused him to leave the project. But viewing the rough cuts of the earlier footage helped bring him back to the project. He remembered how he felt Kazimi was one of the few people he'd ever allow to follow him this intimately, because he felt he could relate to Kazimi as a fellow outsider within the Canadian landscape.

As the film demonstrates, it is difficult to talk about Jeffrey Thomas's photography without talking about Edward Curtis, the European-American photographer who made a name for himself taking portraits of his imagined images of what he felt Native Americans should look like. Thomas's initial approach to his work through Curtis's work is that of frustration when not outright anger. The communities Curtis visited were quite westernized when Curtis arrived, so Curtis staged many of the photographs to meet his required visions of how these Native Americans should look. In other words, they had to meet his stereotypes. Plus, Curtis followed a tradition of early ethnographers who came into indigenous communities, took what they wanted, but never returned to give anything back. The subjects of the photos were never paid and no photos were brought to them in return. In response to these images, Thomas's life's work was to represent the First Nations Peoples as they are now, not as they are imagined in Westerns or other iconic images controlled by institutions outside the First Nations community. One way Thomas controls the images is to place pictures of First Nations Peoples at various pow-wow events dressed up in traditional clothing amongst images of First Nations Peoples in their everyday clothing of jeans and t-shirts at the very same event. This disallows a static image of his people, demanding a more fluid, fluxing, non-stereotypical icon to emerge.

Shooting Indians had me thinking back to my first year in San Francisco when I attended an exhibition at the old Ansel Adams Photography Museum that used to be located on 4th Street between Folsom and Howard. Part of the exhibit was a series of photos of Native Americans taken by European-Americans juxtaposed against photos of Native Americans taken by Native Americans themselves. I have no way of confirming if these were images from the same exhibit curated by Jeffrey Thomas such as the one represented in this film, but I have a strong feeling what I witnessed back then was exactly that. That exhibit is partly responsible for why this Cleveland boy supports his hometown baseball team without displaying the racist Chief Wahoo emblem, instead wearing the cursive "I" used for holiday and Sunday home games. Kazimi helped me recover the memory of that exhibit that I hadn't purposely hidden, but hadn't recalled for some time.

And like my memory, Kazimi's filmmaking process has been anything but smooth. Although he has much praise for the National Film Board of Canada, an exemplary funding organization, and although he knows that his lot is better than his documentary-making friends in India, Kazimi still has run into his own problems. Distribution has been a particular burr in his side. The powers that slot documentaries on Canadian television wanted Kazimi to edit down Continuous Journey even though it was well within the usual length for films aired on the channel. Kazimi took this as an underhanded tactic to force him to get rid of the sobering portrayals of the less than honorable White Canadian populace of the time, portrayals to which some officials took offense. But the National Film Board of Canada provides its funding with flexible strings attached, so though he kept his film true to his vision, it was aired at an hour less hospitable to the average viewer.Besides these political and economic obstacles, there were the general obstacles of the filmmaking process. I've already mentioned how Kazimi was shooting Shooting Indians for 12 years due to the disappearance of his subject. Creating Continuous Journey had its own obstacles because there was very little archival footage from which to work. This required Kazimi to repeat images in his film more often than I'm sure he wanted. But his tireless archival work resulted in two choice finds that have strongly affected audiences. The first is the "White Canada Forever" popular pub song that shocks Canadian audiences when they hear it. Many Canadians have taken great pride, justifiably so, in thier progressive multicultural policies. But to discover this bit of hidden celebratory racism is quite a jolt to the national consciousness.

The second moment is the moving highpoint of moving images in Continuous Journey. It is the kind of surprise moment in a film I don't even want to reveal here in this non-review format where Spoiler!-warnings don't apply. I restrain myself because my hope is that readers will seek out their own chance to see this film. (It is available for purchase on his website.) Perhaps you will experience the same moment of cinematic awe that my fellow ticket-paying travelers did when we saw it together at the 2005 San Francisco Asian-American International Film Festival. Such are those collective connections one only has in the theatre, keeping us coming back again and again. But since this is likely to be a film not coming to a theatre near you, you'll have to settle for such an awe-full moment of an awful moment in Canada's history through the DVD format, the medium where this film's journey continues.

Thursday, October 19

What Is It? and other questions

This weekend is Crispin Hellion Glover weekend here in Frisco. Not only is the multifaceted artist bringing to the Castro Theatre three evening presentations of his controversial, finally-complete experimental film What Is It?, accompanied by his slide show presentation and a question-and-answer session with the audience, but there will also be an eight-film retrospective of his acting work matinees and midnights. From his Reagan-era roles in River's Edge and the jaw-dropping the Orkly Kid to more recent starring roles in the Herman Melville update Bartleby and the Willard remake, Glover's career highlights will finally be shown together on the largest screen possible. And if you can't bear a Crispin Glover weekend without seeing David Lynch's Wild At Heart, it will be playing at the Clay Theatre midnights Friday and Saturday (unfortunately, unless you can enlist the aid of Doc Brown and his Delorean, you'll have to give up one of the Castro midnight screenings to see it.)

This weekend is Crispin Hellion Glover weekend here in Frisco. Not only is the multifaceted artist bringing to the Castro Theatre three evening presentations of his controversial, finally-complete experimental film What Is It?, accompanied by his slide show presentation and a question-and-answer session with the audience, but there will also be an eight-film retrospective of his acting work matinees and midnights. From his Reagan-era roles in River's Edge and the jaw-dropping the Orkly Kid to more recent starring roles in the Herman Melville update Bartleby and the Willard remake, Glover's career highlights will finally be shown together on the largest screen possible. And if you can't bear a Crispin Glover weekend without seeing David Lynch's Wild At Heart, it will be playing at the Clay Theatre midnights Friday and Saturday (unfortunately, unless you can enlist the aid of Doc Brown and his Delorean, you'll have to give up one of the Castro midnight screenings to see it.)I was invited to interview Glover about What Is It? on the Castro Theatre balcony a couple weeks ago. What follows is the first-ever Hell On Frisco Bay artist interview. I've edited out my star-struck stammering but have tried my best to leave the conversation very close to the way it actually happened:

Hell on Frisco Bay: You've been working for years on this film.

Crispin Glover: Yes.

HoFB: Did it evolve in shape and scope, or is it how you envisioned it from the get-go?

CG: Both, because originally it was going to be a short film to promote the concept of working with a cast the majority of whom would be actors with Down's syndrome. I was interested in selling a certain script to a corporation to another film I was going to direct, and they were concerned about the concept, so I wrote a short movie to promote this idea. The initial structure of a simple hero's journey story structure: somebody in their normal world being disturbed, having to go out of that world into a special world, find allies and enemies, and in the end learn a lesson...all of that sits within this film. What the character was going through changed vastly as it turned into a feature film, and then again when I put myself in, and the Steven Stewart character who is the fellow with cerebral palsy that chokes me to death. He's the main character and author of the second film [It Is Fine. Everything Is Fine!], which I'm very close to finishing.

HoFB: So after What Is It? we can look forward to that.

CG: I'm hoping. I never really like to say specifically because things can take longer than you think, but I'm hoping it will be relatively soon.

HoFB: It sounds like What Is It? started with an almost ideological desire to make a film with a particular kind of cast. It's certainly a rare thing to see characters with Down's syndrome played by actors with Down's syndrome in a feature film.

CG: Well, that's something I differentiate specifically though. When I was casting, I made it very clear to the people that I was working with that the film isn't about Down's syndrome and they're not playing characters that have Down's syndrome. It isn't about Down's syndrome. I was questioned about it a lot because the screenplay always had a lot of violence in it, and a lot of the guardians were concerned about the inaccurate portrayal of people with Down's syndrome as violent and the truth of it is that they're generally very genteel people and very nice people to work with. So I always make it exceedingly clear.

The fact of it is that really, the film is about my psychological reaction to certain restraints that are going on in corporate-financed film and the lack of taboo that I think is an extremely important barometer of what the culture is generally thinking about. It's being averted by corporate entities concerned that they're going to make audiences uncomfortable and lose money in the long run, and it ends up stupefying the culture. It's not a good thing. What's unusual is to see people with Down's syndrome making up the majority of the cast of a film and playing the lead roles. When I look into the face of somebody that has Down's syndrome I see, automatically, the history of someone who has lived really outside of the culture, and you can feel something from that when almost the whole film is made up of actors who have that quality.

The fact of it is that really, the film is about my psychological reaction to certain restraints that are going on in corporate-financed film and the lack of taboo that I think is an extremely important barometer of what the culture is generally thinking about. It's being averted by corporate entities concerned that they're going to make audiences uncomfortable and lose money in the long run, and it ends up stupefying the culture. It's not a good thing. What's unusual is to see people with Down's syndrome making up the majority of the cast of a film and playing the lead roles. When I look into the face of somebody that has Down's syndrome I see, automatically, the history of someone who has lived really outside of the culture, and you can feel something from that when almost the whole film is made up of actors who have that quality.HoFB: It seems like the film is an opposite of what we normally see in American films. Aesthetically, thematically, structurally, it's the complete opposite.

CG: A lot of people have said that. I agree, because there is the taboo element; it is what is not allowed and it genuinely does feel quite different because it is ubiquitous; you cannot at this point in time get funding from corporations if a film has any of those qualities at all. If you have one element they will not, even just one. This film has way more than one, so that makes it feel very different.

HoFB: Do you feel you're part of a tradition of oppositional cinema?

CG: Yes, absolutely. I don't feel like I'm breaking ground at all. I feel like I am reacting to this culture specifically. It is not something that has necessarily happened so much. I know there are people that want to react, and it's very difficult in this culture because it's expensive, and then you have to have distribution. I'm in a unique position from having worked in corporately-funded media so it does make it easier for me to contact media. If I didn't have that history and I made this very same film there's no way I would be able to get the kind of attention from media that I'm able to get. It's unfortunate because I'd still stand by the film if I was not. But there is definitely an integral part that I'm reacting to, and I've been part of that. It's been a part of my life so there's a genuine truth to it and genuine frustration that I've dealt with first-hand so it doesn't feel fake.

HoFB: It seems like a big part of the genesis of the themes and structure of the film is your place in the world, which is of course marked by your life in Hollywood as an actor.

CG: That's right. There is definitely an autobiographical element to the film, and there should be. People should make movies about what their experiences are. Often actors will write books or they'll make movies and it generally isn't about what their genuine experience is, and this one is really about that. Of course, it's poetically done so it's not like me walking into a casting office or a business meeting and having a particular discussion but I think the concepts -- ultimately it depends on the person, it seems like you're particularly sensitive to it, and some people just can't make any sense out of it all. It's rarer; most people do make some kind of sense of it, but it sounds like you're picking up on very specific things.

HoFB: I think it's definitely helped for me to have heard and read and talked about the film beforehand, and then I was able to view the film through that lens.

CG: That's one of the reasons that I go and talk about it. On some level, it's cheating because really a film should stand on its own one hundred per cent. It's one of the reasons why Rainer Werner Fassbinder's sensibilities are interesting to me. I discovered his filmmaking while I was working on this. I hadn't locked the film, but I was late in the process. Among the many things I admire about his filmmaking are the socio-economic, political, psychological commentaries that exist within the structures of his films, how clearly he understood those structures and how well he was able to illustrate those psychologies, the political/monetary backgrounds, and what they meant. It's extremely intelligent, extremely perceptive. I haven't seen another filmmaker that's come anywhere near the dynamic realms that he's gone into. It's unusual how intelligent that filmmaking is.

HoFB: You're making me think of Fox and His Friends.

CG: Fox and His Friends has it, Berlin Alexanderplatz has it, Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven has it. He has it all the time, and I felt an obligation to ask myself, "what is this meaning specifically within the culture?" I felt the obligation to clarify in my own mind what some of these poetic things mean, because often I'll view something with an emotional reaction. I ask myself, "why am I reacting to that?"

CG: Fox and His Friends has it, Berlin Alexanderplatz has it, Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven has it. He has it all the time, and I felt an obligation to ask myself, "what is this meaning specifically within the culture?" I felt the obligation to clarify in my own mind what some of these poetic things mean, because often I'll view something with an emotional reaction. I ask myself, "why am I reacting to that?"HoFB: Fassbinder is definitely a kind of oppositional filmmaker, but aesthetically he's a lot less radical than what you're doing.

CG: Maybe. Cinematically, Herzog, Kubrick and Buñuel, really those filmmakers are more cinematic filmmakers, particularly Kubrick and Herzog.

HoFB: Fassbinder is cinematic, he's just not as...

CG: Fantastical.

HoFB: Yeah, exactly.

CG: But you can see later on he started working with sets, in his last film, Querelle. It's not my favorite of his films. Also he didn't finish it. There's a narration in it. When he narrates his own films, like the narration he does in Berlin Alexanderplatz which I think is my favorite narration I've ever heard in film, it's just so psychologically integrated into the moments, and he's a great performer, and intelligent. It's just phenomenal. In Querelle they have like an American narrator voice narrating this stuff. You just know if he'd finished the film it would've been a very different thing. His last film I think he was alive to finish was Veronika Voss, which had a beautiful look to it. He was so young when he died. It's really a tragedy. The amount of work that he did in his life; he made more films than years he lived, and one of those films is Berlin Alexanderplatz, which is fifteen hours long. I feel that if he had remained alive the face of cinema at this point in time would be totally different because he would have reacted to these very things that I believe are going on right now. I really do admire him very much.

HoFB: Is there anyone you would point to in the tradition you're operating in psychologically?

CG: Buñuel. L'Age D'Or specifically. I have my analysis of that film, and I think he was very much reacting to a Catholic-based situation. I feel these reactions in the film. It's maybe overlooked now, because these reactions are not necessary at this point in time. At that time when he was in Europe, Catholicism was pretty overwhelming. He grew up in Spain, so he definitely had that reaction his whole life, and it was a valuable thing for him to do, and it made sense for him. I don't live in a Catholic culture. It wouldn't make sense for me to be reacting to that. I live in a very different, maybe a little bit more difficult to define, or maybe certain things shouldn't be defined because if you define them you can get in real trouble, but there are different things that I'm reacting to, different control elements other than Catholicism.

CG: Buñuel. L'Age D'Or specifically. I have my analysis of that film, and I think he was very much reacting to a Catholic-based situation. I feel these reactions in the film. It's maybe overlooked now, because these reactions are not necessary at this point in time. At that time when he was in Europe, Catholicism was pretty overwhelming. He grew up in Spain, so he definitely had that reaction his whole life, and it was a valuable thing for him to do, and it made sense for him. I don't live in a Catholic culture. It wouldn't make sense for me to be reacting to that. I live in a very different, maybe a little bit more difficult to define, or maybe certain things shouldn't be defined because if you define them you can get in real trouble, but there are different things that I'm reacting to, different control elements other than Catholicism.HoFB: It's interesting how Buñuel did it in different ways at different points in his career. At first he was doing it very aesthetically radically with Dali, but later in films like Viridiana it's a more a narrative approach.

CG: And they're fantastic. I hesitate to call things narrative or non-narrative. All of Buñuel's films are narrative. What is It? was at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, the oldest experimental film festival in the US, and it won Best Narrative Film. This is a narrative film, but it is in the tradition of the vocabulary that Buñuel was working with in his early career. I see clearly those poetic realms, but you have to work in those poetic realms if you really feel that you could be offending people sometimes. Buñuel had to work poetically because if he just made a film that specifically attacked Catholicism he would have been in even much greater peril. There was some genuine peril. People got mad! They didn't just think this was a nice little fun film. He produced the film in Spain and then he had to leave Spain because of Franco. That's why he went to Mexico and that's when he started directing films again. And it is great to see how he changed. And it's something that I've thought about a lot. Certainly, all of the films that I'm interested in making are not in this exact same kind of vocabulary.

HoFB: It seems like even your acting work in the past has sometimes dealt with the audience's stance in regard to celebrity, like in The Orkly Kid, or Nurse Betty, or even that line in Rubin & Ed where Rubin talks about "famous frauds". It seems that, especially in The Orkly Kid, you haven't been afraid of looking at ways the general public relates to celebrity.

HoFB: It seems like even your acting work in the past has sometimes dealt with the audience's stance in regard to celebrity, like in The Orkly Kid, or Nurse Betty, or even that line in Rubin & Ed where Rubin talks about "famous frauds". It seems that, especially in The Orkly Kid, you haven't been afraid of looking at ways the general public relates to celebrity. CG: Yeah, and What Is It? definitely has something about celebrity. It's a funny thing, because I've known people that are, you know, very well-known, and there is a business to celebrity-dom. It's peculiar to me if somebody doesn't realize that. Celebrity does change one's reality; even I see that there's kind of a warped sensibility of things. Everybody to a certain extent is warped by whatever their own reality is, if you want to call it "warped". It's a pejorative but it doesn't need to be. There is something that can be played with. I think Andy Kaufman played with celebrity in ultimately a very intelligent fashion, but if one plays with it people can become very confused.

I feel like the persona that is put forth by some of the most well-known celebrities, who are very much in control of that persona, is often quite the opposite of what their real self is, and probably their own mind's eye of themselves, and that one of the reasons that they want to put this other persona so far forward is because they really don't feel like that about themselves. I feel that often, though not always, people that constantly play a heroic type of persona are actually cowardly, whereas I feel like it's a very brave person who plays the cowardly person, or the person that is not viewed as the best person or the good person or the person that one wants to be. Of course it isn't one hundred percent true. There are great performers who have played heroic people, but I think that often times it isn't that way.

HoFB: I think that everyone, celebrity or not, does it to some degree. Takes on a persona.

CG: Sure, sure. And there are positive things to it too. You want to be the best person you can be, hopefully. Or you want to be the worst person, if that's your persona.

HoFB: It seems you tend to play characters that are not always the "best person". They're often very subversive.

CG: Yeah, I find those characters really interesting to play. Sometimes when I play the characters that are a little less eccentric or something, I wonder, is that as interesting to me personally? I mean, I should do those. Sometimes it's good for me. I mean, like the Nurse Betty character I played was definitely an example, but I enjoyed very much working with Neil LaBute. He was really a great director and I'm really glad I did that film, but I remember thinking, "this good guy I'm playing isn't that...odd."

HoFB: Do you feel closer to the eccentrics?

CG: It depends. On some levels I don't feel eccentric at all. I dress fairly conservatively. I actually I have a good standard of living, my property in the Czech Republic, my house. I have some nice antique cars. I've acquired a certain amount of things, but really most of my monies are going toward making my films now. But, I try to go to nice restaurants if I'm going to go out, or cook food for myself that's healthy. You know, those kinds of things that are normal.

HoFB: You've got a niche in American acting, where you draw people who wouldn't normally be drawn to Hollywood films like Charlie's Angels.

HoFB: You've got a niche in American acting, where you draw people who wouldn't normally be drawn to Hollywood films like Charlie's Angels.CG: That I consider a positive, definitely. That is a good thing and it's something that I count on for this film, for touring around. I know there are people that have become interested in seeing me, and I'm very grateful for that. Now I'm touring around with the film and I really am cutting out the middleman. I'm working directly with the audience that is coming in and paying the money to the box office. Ultimately those people are paying me back directly for the investment I've made in this film. I don't have a corporate, intervening middleman that comes between me and the audience. So I am extremely understanding that each one of those people that comes in is helping me out, and it's a very direct relationship. When I'm doing the book signings and I'm personally talking to each person, I'm quite grateful to that person. It's a very direct working relationship with -- I don't even like the word "fan base", but whatever you want to call it. People that are interested in your work.

HoFB: One last question: It seems that, increasingly, the way that economic transactions take place in the film world is through the sale of DVDs. I understand you're not going to be making a DVD of What Is It? available.

CG: It's hard to know what will happen, but right now I have zero plans for it. I want to continue touring around with it for years to come, and I have a concept of growing a library that I can keep touring around with, because I know everybody that wants to won't be able to see it on those three days in San Francisco that I'm here. If I come back next year or later with another film and I have this film with it, some other people can come that didn't get to see What Is It? before. Or, if somebody's interested in seeing it again. Because I know I like looking at a certain kind of film over and over again, and I want to make films to see over and over again, that you want to see projected in a theatre like the Castro.

End of interview.

What Is It? screens at the Castro Theatre with Crispin Glover appearing in person at 7:30 PM on October 20, 21 and 22. The Crispin Glover Film Festival will be held at the same theatre on those dates.

Monday, October 16

Robert Aldrich Blog-A-Thon: Apache

I apologize for the long silence on this blog; I can't believe it's already been more than three weeks since my last post. Some of that time has been spent watching movies but it still feels like I've missed an awful lot. For example I unfortunately ended up seeing only a single solitary film from the Mill Valley Film Festival lineup, the one I was able to catch at an advance screening here in Frisco: The Queen. This shiny new Oscar hopeful ought to satisfy just about anyone looking for an intelligent film, but will probably disappoint anyone looking for a brilliant one. Of course, intelligent films are rare enough that I expect this one to do very well against its as-yet unseen competition.

I apologize for the long silence on this blog; I can't believe it's already been more than three weeks since my last post. Some of that time has been spent watching movies but it still feels like I've missed an awful lot. For example I unfortunately ended up seeing only a single solitary film from the Mill Valley Film Festival lineup, the one I was able to catch at an advance screening here in Frisco: The Queen. This shiny new Oscar hopeful ought to satisfy just about anyone looking for an intelligent film, but will probably disappoint anyone looking for a brilliant one. Of course, intelligent films are rare enough that I expect this one to do very well against its as-yet unseen competition.Arranging trips to Mill Valley or San Rafael is difficult enough but the past few weeks I've been stretched particularly thin. I hope I can figure a way to make it to the latter venue for an October 26 screening of the Magnificent Ambersons and at least one or two of the Otto Preminger films playing the first weekend of December. I'm disappointed I missed films argued for so beautifully in places like here and here, but I didn't want to pass up an opportunity to go on a road trip to the Lone Pine Film Festival with my dad and then report on it for Greencine Daily. One real highlight of attending the festival was getting a chance to meet and talk movies with one of the best filmbloggers on my sidebar, Dennis Cozzalio of Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule. Dennis is hosting a Robert Aldrich Blog-A-Thon today, but since I've already got several unfinished pieces I want to finish up and publish here this week, I'd all but given up on the idea of contributing, especially since I'd only seen the director's two most widely-esteemed films, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and Kiss Me Deadly. But then I read about the difficulties preventing fellow blogger Girish Shambu from contributing a post to today's event, and I realized that I had no good excuse not to come up with something, however lame. I popped in a previously unwatched videocassette of Aldrich's 1954 Apache to see what I thought of it on a first viewing. What I've come up with is far less a contribution to the blogosphere's Aldrich-knowledge than an apology explaining why I emerged from a viewing of a Robert Aldrich film without having much of anything to say about Robert Aldrich.

Though my decision to pick Apache from among all Aldrich films to watch and write about is essentially due to happenstance (it was the one title of his I had conveniently lying around the house), I also thought it might be fortuitous to look at a film in the genre (the Western) that was also the focus of the film festival I'd just attended and written about. My fascinations with film genres in which a talented auteur director might be easily able to slip in touches more interesting and unexpected than in a Hollywood "prestige" picture have led me to become particularly interested in Westerns, but not to the point of becoming any kind of an authority on them as my exposure is still too narrow. Focusing a large portion of my film-watching efforts on the offerings available on Frisco cinema screens has helped to ensure that; Westerns simply don't get screened in this town very often. Even those of the spaghetti variety, like the Leone films playing the Castro next Tuesday and Wednesday, aren't seen terribly often here. So after a weekend at Lone Pine I've definitely been spending more time than usual considering Westerns, and particularly the way they portray American Indian tribes.

But nothing could really have prepared me for the utter preposterousness of seeing Apache's stars Burt Lancaster and Jean Peters in Technicolor "redface" makeup for ninety minutes. (Angelina Jolie might do well to look at this movie right about now.) Well, perhaps I could have eventually gotten used to it if the dialogue and acting weren't so stiff and humorless (Lancaster's Massai makes a single joke toward the end of the film when he places a tiny cornstalk up to his ear, but even that feels like far too weighty a moment), or if the history lessons weren't so bizarre in their inaccuracy. The film's premise rests on an understanding that Geronimo's Apaches (and, as the film implies, all other tribes as well) had no knowledge of farming until they were introduced to it by whites. The screamingly ludicrous symbol of this is a sack of seed corn (corn!!!) given to Massai by an Oklahoma Cherokee with the intention of helping him mimic white culture.

But nothing could really have prepared me for the utter preposterousness of seeing Apache's stars Burt Lancaster and Jean Peters in Technicolor "redface" makeup for ninety minutes. (Angelina Jolie might do well to look at this movie right about now.) Well, perhaps I could have eventually gotten used to it if the dialogue and acting weren't so stiff and humorless (Lancaster's Massai makes a single joke toward the end of the film when he places a tiny cornstalk up to his ear, but even that feels like far too weighty a moment), or if the history lessons weren't so bizarre in their inaccuracy. The film's premise rests on an understanding that Geronimo's Apaches (and, as the film implies, all other tribes as well) had no knowledge of farming until they were introduced to it by whites. The screamingly ludicrous symbol of this is a sack of seed corn (corn!!!) given to Massai by an Oklahoma Cherokee with the intention of helping him mimic white culture.The gaping erroneousness throws the entire film off-balance, to the point where it's difficult to unpack just what messages are being sent, other than misinformation. There are attempts to bring up issues like assimilation and cultural relativity, but they can't really go anywhere. Still, it's worth watching the engine of Hollywood narrative techniques for once applied to get us rooting for a character who in most Westerns would be an unqualified villain. Massai's freedom fighting often resembles terrorism but the deck is stacked to have the audience feel the maximum amount of pity for his tragic character. By the end of the film he turns himself in and lives happily ever after, which I understand departs from the actual, more tragic fate of the historical inspiration for the character. It made me think of the requirements of the Hollywood Production Code. It seems unlikely that a film with the stance of Apache could have been made much earlier than 1954, by which point the code was starting to become a little less tight of a straightjacket in its requirements for the depiction of protagonists. But at the same time there's no way filmmakers working under the code could ever consider showing the truth of the worst atrocities committed against Indians, as it would mean terrible crimes would have to go unpunished. One Code-friendly option could have been to show the crimes and then punish them, but that would go against the sweep of a history in which perpetrators of such crimes have long gotten away with their misdeeds.

There is my reaction to a single viewing of Apache. It would take a far greater investment of study of the film and of other Aldrich films for me to be able to look past the biggest stumbling blocks I found in this film, primarily the 1954 convention of casting white actors in non-white roles, the stereotyped dialogue, and Hollywood-style rewriting of history. I hope to inch my way closer to a better understanding of Aldrich and what exactly he brought to the table through the other entries in today's Blog-A-Thon, but to be honest I'm not too eager to revisit Apache anytime soon. In fact, I feel more like running in exactly the other direction from Hollywood depictions of American Indians right about now. Which means the 31st Annual American Indian Film Festival coming to the Lumiere and the Palace of Fine Arts Nov 3-11, including a screening of the Journals of Knud Rasmussen Nov. 9, can't arrive soon enough!

There is my reaction to a single viewing of Apache. It would take a far greater investment of study of the film and of other Aldrich films for me to be able to look past the biggest stumbling blocks I found in this film, primarily the 1954 convention of casting white actors in non-white roles, the stereotyped dialogue, and Hollywood-style rewriting of history. I hope to inch my way closer to a better understanding of Aldrich and what exactly he brought to the table through the other entries in today's Blog-A-Thon, but to be honest I'm not too eager to revisit Apache anytime soon. In fact, I feel more like running in exactly the other direction from Hollywood depictions of American Indians right about now. Which means the 31st Annual American Indian Film Festival coming to the Lumiere and the Palace of Fine Arts Nov 3-11, including a screening of the Journals of Knud Rasmussen Nov. 9, can't arrive soon enough!