Monday, May 15

Century Deprivation

In my ongoing quest to understand motion pictures at their most fundamental level, I find I have an almost insatiable appetite for films from earlier eras. It wasn't always so; I used to be so overwhelmed by my lack of familiarity with classical cinema canon that I fled into an obsessive interest in only the newest releases. It was only a little over five years ago that I started a project of trying to semi-systematically familiarize myself with the films and filmmakers of yesteryear. I'm still working on that project, I guess, though its systematic nature has gradually dissipated; now I follow my interests more than I do lists like this one.

As a celluloid...if not purist let's say proponent, I also take my cues from the cornucopia of repertory programming found in Frisco theatres. And film festivals have been a crucial component of that feast. The SFIFF in particular has helped me fill many crucial gaps in my cinema history self-education, especially through its awards presentations. Seeing the complete Magick Lantern Cycle at the Castro when Kenneth Anger was given the Persistance of Vision Award in 2001, or Come to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean when Robert Altman got the festival's Directing Award in 2003 were among the highlights. So, as excited as I was for an opportunity to view Directing Award recipient Werner Herzog's latest film the Wild Blue Yonder at this year's festival, I was disappointed to learn that no prints of the films that Herzog's reputation was made and sustained by would show as part of the festival (while, as I learned of via Greencine Daily, the recent Sarasota Film Festival was able to mount an envy-inducing series just a few weeks earlier). My disappointment was slightly tempered at the event itself by several factors: festival director Graham Leggat's reminder in his introduction that many of the rarer entries in his filmography are now packaged in a DVD box set available for order on Herzog's own website, Herzog's on-stage admission that good prints of many of his films have not been properly preserved (which brought on a note-to-self reminder to follow up on this problem with Eastman House), and the stunning beauty of the images in the Wild Blue Yonder, which should be enough to tide me over for a little while.

As a celluloid...if not purist let's say proponent, I also take my cues from the cornucopia of repertory programming found in Frisco theatres. And film festivals have been a crucial component of that feast. The SFIFF in particular has helped me fill many crucial gaps in my cinema history self-education, especially through its awards presentations. Seeing the complete Magick Lantern Cycle at the Castro when Kenneth Anger was given the Persistance of Vision Award in 2001, or Come to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean when Robert Altman got the festival's Directing Award in 2003 were among the highlights. So, as excited as I was for an opportunity to view Directing Award recipient Werner Herzog's latest film the Wild Blue Yonder at this year's festival, I was disappointed to learn that no prints of the films that Herzog's reputation was made and sustained by would show as part of the festival (while, as I learned of via Greencine Daily, the recent Sarasota Film Festival was able to mount an envy-inducing series just a few weeks earlier). My disappointment was slightly tempered at the event itself by several factors: festival director Graham Leggat's reminder in his introduction that many of the rarer entries in his filmography are now packaged in a DVD box set available for order on Herzog's own website, Herzog's on-stage admission that good prints of many of his films have not been properly preserved (which brought on a note-to-self reminder to follow up on this problem with Eastman House), and the stunning beauty of the images in the Wild Blue Yonder, which should be enough to tide me over for a little while.

It's clear that the festival's Directing Award, which counted the "esoteric" and "unpronounceable" (Ruthe Stein's words, not mine) likes of Im Kwon-Taek and Manoel de Oliveira among its recipients back in the days when it was called the Akira Kurosawa award, now plays a role in the film society's prestige among the general public that precludes it from being bestowed upon directors well-known in this country only among hardcore cinephiles. That said, Herzog is one of the true iconoclasts among famous directors working today, and therefore a perfect choice for the award. But it's worth noting that his filmography is laden with at least as many great documentaries as fiction films, even if he famously likes to downplay the difference between these two categories, and did so again when interviewed before the screening, claiming "It's all movies for me." With his documentary, short film and television credentials, Herzog could instead have snugly received the festival's Persistance of Vision Award, which annually honors the career of a filmmaker for working outside the "feature film" sphere. The actual recipient of the award this year was Guy Maddin, another figure whose work fits both inside and outside that sphere. His most widely-seen film is almost certainly the Saddest Music in the World starring Isabella Rossellini but he also has made films for television (Dracula: Pages From a Virgin's Diary) and a good deal of short films, several of which were interspersed with a live interview between Maddin and Steve Seid of the Pacific Film Archive.

The interview demonstrated Maddin to be an incredibly funny and down-to-earth guy, the complete opposite from the über-pretentious aesthete you might think would be the type to name one of his films Odilon Redon or the Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity. I was thrilled to see Maddin's newest film, My Dad is 100 Years Old and doubly thrilled to finally see The Heart of the World, which I had so ruefully missed when it played the 2001 SFIFF, projected onto the Kabuki Theatre's grandest screen (I certainly hope House 1 is not seriously overhauled in the remodel being undertaken by the theatre's new owner.) The Heart of the World equals the visual and narrative complexity of all but the most Byzantinely-plotted feature films, but it packs all its images into the space of six minutes, which is why it just might be the most entertainingly rewatchable short film ever. Well, at least since Tex Avery. It helps that, like Artur Pelechian's equally exhilarating The Beginning and the introduction to Soviet television's news program, Maddin's film is driven by Georgy Sviridov's pulsating and instantly memorable music from the 1965 Mosfilm release Time, Forward! Part of me would have liked to hear Maddin talk more about making The Heart of the World and other shorts (the same part of me that wished the Maddin essay in the festival program didn't focus so much on feature films, considering the POV Award is supposedly for everything but), though my more practical side was too giddy over the subjects he did talk about (like this, for example) to care at all.

The interview demonstrated Maddin to be an incredibly funny and down-to-earth guy, the complete opposite from the über-pretentious aesthete you might think would be the type to name one of his films Odilon Redon or the Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity. I was thrilled to see Maddin's newest film, My Dad is 100 Years Old and doubly thrilled to finally see The Heart of the World, which I had so ruefully missed when it played the 2001 SFIFF, projected onto the Kabuki Theatre's grandest screen (I certainly hope House 1 is not seriously overhauled in the remodel being undertaken by the theatre's new owner.) The Heart of the World equals the visual and narrative complexity of all but the most Byzantinely-plotted feature films, but it packs all its images into the space of six minutes, which is why it just might be the most entertainingly rewatchable short film ever. Well, at least since Tex Avery. It helps that, like Artur Pelechian's equally exhilarating The Beginning and the introduction to Soviet television's news program, Maddin's film is driven by Georgy Sviridov's pulsating and instantly memorable music from the 1965 Mosfilm release Time, Forward! Part of me would have liked to hear Maddin talk more about making The Heart of the World and other shorts (the same part of me that wished the Maddin essay in the festival program didn't focus so much on feature films, considering the POV Award is supposedly for everything but), though my more practical side was too giddy over the subjects he did talk about (like this, for example) to care at all.

I do feel a bit like I'm needlessly nitpicking by trying to demonstrate that Herzog and Maddin could easily have switched awards, if not for the fact that Herzog has the greater and wider reputation. I just think it's worth pointing out that in the past few years the festival has really had two awards for directors: one for big-names and one for lesser-knowns who, like most filmmakers, happen to have some shorts, documentaries, animation, and/or TV work under their belts. I don't mind as long as both choices are good ones; "it's all movies for me." And this year was nothing like 2002, where it was clear to any discerning cinephile that the director of greater stature if not international fame (Fernando Birri) was receiving the "less prestigious" award while a director of three and a half films (not to disparage the quality of Bulworth, which I really like) got the bigger-billed one. I've long since wondered if it was more than coincidence that it was after that year that the Kurosawa estate wanted the name of the award back.

I missed the big events for Peter J. Owens Award recipient Ed Harris and Kanbar Award recipient Jean-Claude Carrière, the latter especially to my great regret. But the festival made what I thought were very appropriate selections of screenings to accompany the q-and-a sessions: a Flash of Green for Harris and Belle De Jour for Carrière. A Flash of Green is one of two films I've seen by Floridian director Victor Nunez, and like Ulee's Gold, which helped Peter Fonda grab a Golden Globe award, it's a showcase for a lead actor, in this case Harris, to construct a character of uncommon richness for a two-hour movie. As such it's a good choice to accompany presentation of an acting award, even if as a film it isn't quite as tightly-structured as Ulee's Gold is. And though I've seen too small a sample of Jean-Claude Carrière's career to feel confident in calling Belle De Jour his crowning achievement (rivaled in my mind only by the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), it is a self-reflexive masterpiece of cinematic illogic. It's also the only Carrière-Buñuel collaboration withheld from a brief series that played the Castro during the last few months of Anita Monga's stewardship of that theatre in 2004, and was therefore was ripe for a Frisco theatrical viewing.

I missed the big events for Peter J. Owens Award recipient Ed Harris and Kanbar Award recipient Jean-Claude Carrière, the latter especially to my great regret. But the festival made what I thought were very appropriate selections of screenings to accompany the q-and-a sessions: a Flash of Green for Harris and Belle De Jour for Carrière. A Flash of Green is one of two films I've seen by Floridian director Victor Nunez, and like Ulee's Gold, which helped Peter Fonda grab a Golden Globe award, it's a showcase for a lead actor, in this case Harris, to construct a character of uncommon richness for a two-hour movie. As such it's a good choice to accompany presentation of an acting award, even if as a film it isn't quite as tightly-structured as Ulee's Gold is. And though I've seen too small a sample of Jean-Claude Carrière's career to feel confident in calling Belle De Jour his crowning achievement (rivaled in my mind only by the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), it is a self-reflexive masterpiece of cinematic illogic. It's also the only Carrière-Buñuel collaboration withheld from a brief series that played the Castro during the last few months of Anita Monga's stewardship of that theatre in 2004, and was therefore was ripe for a Frisco theatrical viewing.

The Mel Novikoff Award "for enhancing the public's awareness and enjoyment of film" that Monga recieved at the 2005 edition of the festival was not given out at this year's edition. I thought this was a bit of a shame, not only because I support the spirit of an award given to film programmers, preservationists, critics, and other people in the film community besides the filmmakers awarded by so many other groups, but also for the purely selfish reason that the award has traditionally provided an opportunity to see some of the most intriguing and hard-to-find films the festival has screened in the past few years. The collection of silent shorts Paolo Cherchi Usai picked out in 2004 (which I caught, and which turned me into a Charley Bowers fan), or the mini-retro for Jacques Rozier brought by Cahiers du Cinéma when it was awarded in 2001 (which I missed, and which hasn't made a return visit to the area) are just a few examples.

Instead, Monga was offered a carte blanche programming selection by the SFIFF. She decided to bring a print of Hal Roach's 1940 gender-bender comedy Turnabout, a glimpse of the UCLA Film and Television Archive's biennial festival of preservation happening in Los Angeles this July and August. This festival sounds well worth a road trip, especially since I unfortunately missed both screenings of Turnabout, one due to my work schedule and the other because I felt compelled to see the Alloy Orchestra's second-ever public performance of a newly-composed score to the 1925 Rudolph Valentino vehicle, The Eagle. Directed by Clarence Brown (one of Andrew Sarris's "subjects for further research"), The Eagle rarely seemed better than average on its own merits, but it's the kind of film that really plays to the Alloys' strongest points: propelling the excitement of action sequences and modernizing melodrama that with a more traditional score might seem unbearable to unaccustomed audiences. The group also performed at a matinee screening of three short films: Buster Keaton's One Week, Fatty Arbuckle's Back Stage, and Jane Gillooly's modern silent Dragonflies, the Baby Cries.

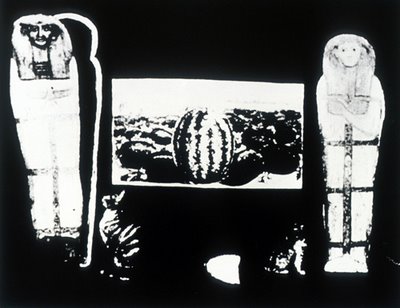

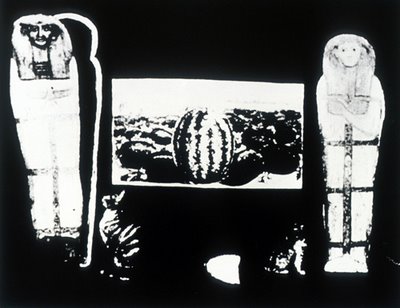

A totally different kind of pairing of live musicians with an underscreened film classic occurred a few days later when Deerhoof took on Harry Smith's 1962 epic of iconography, Heaven and Earth Magic. The SFIFF has made a tradition of bringing some of this century's best American indie rockers together with some of the last century's most eye-popping films since the cusp of the two centuries in 2000, when Tom Verlaine performed in front of a set of surrealist shorts. I've always appreciated the interpretations the musicians have come up with, sometimes very much so, though the purist in me feels that they're often not the best way for someone to be introduced to the films. This time around I was particularly skeptical because Heaven and Earth Magic is not a silent work; it has a soundtrack of library sound effects put together musique concrète-style. On the other hand I knew that the huge Castro screen would display Smith's visuals better than I could possibly hope to see them again, barring re-discovery of the original color version now lost, and when I finally started paying attention to friends who'd been touting Deerhoof to me for years and listened to some of their albums in anticipation of the event, I grew more optimistic.

A totally different kind of pairing of live musicians with an underscreened film classic occurred a few days later when Deerhoof took on Harry Smith's 1962 epic of iconography, Heaven and Earth Magic. The SFIFF has made a tradition of bringing some of this century's best American indie rockers together with some of the last century's most eye-popping films since the cusp of the two centuries in 2000, when Tom Verlaine performed in front of a set of surrealist shorts. I've always appreciated the interpretations the musicians have come up with, sometimes very much so, though the purist in me feels that they're often not the best way for someone to be introduced to the films. This time around I was particularly skeptical because Heaven and Earth Magic is not a silent work; it has a soundtrack of library sound effects put together musique concrète-style. On the other hand I knew that the huge Castro screen would display Smith's visuals better than I could possibly hope to see them again, barring re-discovery of the original color version now lost, and when I finally started paying attention to friends who'd been touting Deerhoof to me for years and listened to some of their albums in anticipation of the event, I grew more optimistic.

I was not disappointed. Deerhoof resisted any temptation they might have had to utilize their ability to rock out and overwhelm Smith's images. Instead they used their instruments, as well as the Castro's Wurlitzer organ that they had to obtain extra-special permission to incorporate, as if they encompassed a gigantic library of sound effects as eerie and off-kilter as the wolf howls and thunder cracks employed by Smith in his original sound track. Sure, they put together a mean rhythm for a section here and a section there, the most memorable being during a scene of whirring gears and orbs toward the end of the film. But they always seemed conscious of the delicate pacing of Smith's animation. When the nourishing meal of Heaven and Earth Magic was finished, the band moved on to provide its fans in the audience with the dessert many of them had been craving: several of Smith's Early Abstractions played on the screen, but instead of the Meet the Beatles! soundtrack long associated with the films, Deerhoof played and sang four songs from its latest album The Runners Four (plus "Flower" from Apple O') and it was a lot of fun. Clearly, the band took care to match each film with the right song. For example, what I think might have been Abstraction No. 4, a film of "black and white abstractions of dots and grillworks" was accompanied by the song "Spy On You", which lent an air of paranoia to the the searching and probing motion of light that makes up the film. I enjoyed these added meanings introduced by the Deerhoof lyrics, though I also am mindful of what Jonas Mekas in his Movie Journal has to say regarding audience reaction to the soundtrack that, as legend has it, he was the one to add to Smith's films:

I was not disappointed. Deerhoof resisted any temptation they might have had to utilize their ability to rock out and overwhelm Smith's images. Instead they used their instruments, as well as the Castro's Wurlitzer organ that they had to obtain extra-special permission to incorporate, as if they encompassed a gigantic library of sound effects as eerie and off-kilter as the wolf howls and thunder cracks employed by Smith in his original sound track. Sure, they put together a mean rhythm for a section here and a section there, the most memorable being during a scene of whirring gears and orbs toward the end of the film. But they always seemed conscious of the delicate pacing of Smith's animation. When the nourishing meal of Heaven and Earth Magic was finished, the band moved on to provide its fans in the audience with the dessert many of them had been craving: several of Smith's Early Abstractions played on the screen, but instead of the Meet the Beatles! soundtrack long associated with the films, Deerhoof played and sang four songs from its latest album The Runners Four (plus "Flower" from Apple O') and it was a lot of fun. Clearly, the band took care to match each film with the right song. For example, what I think might have been Abstraction No. 4, a film of "black and white abstractions of dots and grillworks" was accompanied by the song "Spy On You", which lent an air of paranoia to the the searching and probing motion of light that makes up the film. I enjoyed these added meanings introduced by the Deerhoof lyrics, though I also am mindful of what Jonas Mekas in his Movie Journal has to say regarding audience reaction to the soundtrack that, as legend has it, he was the one to add to Smith's films:  Though I'm hopeful that the SFIFF will decide for next year's historic 50th anniversary to reverse the trend of decreasing revival selections, I'm also thankful that I got to see what I did this year. But truly, my appetite to rediscover classic films amidst the hubbub of a festival setting has only barely been staved off. Which is why I'm so excited about returning to the Castro for the next Silent Film Festival. The schedule has just been fully announced. For a director-centric film lover like me, this 11th year of the festival looks like it might be the best yet. It includes the first Silent Film Fest appearances by great auteurs from John Ford (the 1917 Western Bucking Broadway, introduced by Ford biographer Joseph McBride and Ford actor Harry Carey, Jr. July 15) to G.W. Pabst (a new Louise Brooks centenary print of Pandora's Box, July 15) to Boris Barnet (The Girl With The Hatbox starring the gorgeous half-Ukranian, half-Swedish actress Anna Sten, July 16) to Leo McCarey (three of his Laurel and Hardy two-reelers play July 16.) Frenchman Julien Duvivier's reputation has still yet to bounce back from the hit taken when the nouvelle vague lumped him in with the Tradition-of-Quality filmmakers they liked to sneer at; might Au Bonheur Des Dames (July 15) help kickstart renewed interest in the director? And though I already knew four of the titles selected for the festival, I'm freshly excited about them all over again now that I've learned who's been entrusted with the musical accompaniment: Clark Wilson on organ for the July 14 opening night film Seventh Heaven, Michael Mortilla on piano for the July 15 Sparrows, Jon Mirsalis on piano for July 16th's The Unholy Three, and last but most assuredly not least Dennis James at the organ for the closing film Show People July16.

Though I'm hopeful that the SFIFF will decide for next year's historic 50th anniversary to reverse the trend of decreasing revival selections, I'm also thankful that I got to see what I did this year. But truly, my appetite to rediscover classic films amidst the hubbub of a festival setting has only barely been staved off. Which is why I'm so excited about returning to the Castro for the next Silent Film Festival. The schedule has just been fully announced. For a director-centric film lover like me, this 11th year of the festival looks like it might be the best yet. It includes the first Silent Film Fest appearances by great auteurs from John Ford (the 1917 Western Bucking Broadway, introduced by Ford biographer Joseph McBride and Ford actor Harry Carey, Jr. July 15) to G.W. Pabst (a new Louise Brooks centenary print of Pandora's Box, July 15) to Boris Barnet (The Girl With The Hatbox starring the gorgeous half-Ukranian, half-Swedish actress Anna Sten, July 16) to Leo McCarey (three of his Laurel and Hardy two-reelers play July 16.) Frenchman Julien Duvivier's reputation has still yet to bounce back from the hit taken when the nouvelle vague lumped him in with the Tradition-of-Quality filmmakers they liked to sneer at; might Au Bonheur Des Dames (July 15) help kickstart renewed interest in the director? And though I already knew four of the titles selected for the festival, I'm freshly excited about them all over again now that I've learned who's been entrusted with the musical accompaniment: Clark Wilson on organ for the July 14 opening night film Seventh Heaven, Michael Mortilla on piano for the July 15 Sparrows, Jon Mirsalis on piano for July 16th's The Unholy Three, and last but most assuredly not least Dennis James at the organ for the closing film Show People July16.

I also found out the schedule for the Bronco Billy silent film festival happening a few weekends beforehand, June 23-25 at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum across the bay in Fremont. Programs devoted to Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin and Harold Lloyd jumped out on a brief initial glance.

As a celluloid...if not purist let's say proponent, I also take my cues from the cornucopia of repertory programming found in Frisco theatres. And film festivals have been a crucial component of that feast. The SFIFF in particular has helped me fill many crucial gaps in my cinema history self-education, especially through its awards presentations. Seeing the complete Magick Lantern Cycle at the Castro when Kenneth Anger was given the Persistance of Vision Award in 2001, or Come to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean when Robert Altman got the festival's Directing Award in 2003 were among the highlights. So, as excited as I was for an opportunity to view Directing Award recipient Werner Herzog's latest film the Wild Blue Yonder at this year's festival, I was disappointed to learn that no prints of the films that Herzog's reputation was made and sustained by would show as part of the festival (while, as I learned of via Greencine Daily, the recent Sarasota Film Festival was able to mount an envy-inducing series just a few weeks earlier). My disappointment was slightly tempered at the event itself by several factors: festival director Graham Leggat's reminder in his introduction that many of the rarer entries in his filmography are now packaged in a DVD box set available for order on Herzog's own website, Herzog's on-stage admission that good prints of many of his films have not been properly preserved (which brought on a note-to-self reminder to follow up on this problem with Eastman House), and the stunning beauty of the images in the Wild Blue Yonder, which should be enough to tide me over for a little while.

As a celluloid...if not purist let's say proponent, I also take my cues from the cornucopia of repertory programming found in Frisco theatres. And film festivals have been a crucial component of that feast. The SFIFF in particular has helped me fill many crucial gaps in my cinema history self-education, especially through its awards presentations. Seeing the complete Magick Lantern Cycle at the Castro when Kenneth Anger was given the Persistance of Vision Award in 2001, or Come to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean when Robert Altman got the festival's Directing Award in 2003 were among the highlights. So, as excited as I was for an opportunity to view Directing Award recipient Werner Herzog's latest film the Wild Blue Yonder at this year's festival, I was disappointed to learn that no prints of the films that Herzog's reputation was made and sustained by would show as part of the festival (while, as I learned of via Greencine Daily, the recent Sarasota Film Festival was able to mount an envy-inducing series just a few weeks earlier). My disappointment was slightly tempered at the event itself by several factors: festival director Graham Leggat's reminder in his introduction that many of the rarer entries in his filmography are now packaged in a DVD box set available for order on Herzog's own website, Herzog's on-stage admission that good prints of many of his films have not been properly preserved (which brought on a note-to-self reminder to follow up on this problem with Eastman House), and the stunning beauty of the images in the Wild Blue Yonder, which should be enough to tide me over for a little while.It's clear that the festival's Directing Award, which counted the "esoteric" and "unpronounceable" (Ruthe Stein's words, not mine) likes of Im Kwon-Taek and Manoel de Oliveira among its recipients back in the days when it was called the Akira Kurosawa award, now plays a role in the film society's prestige among the general public that precludes it from being bestowed upon directors well-known in this country only among hardcore cinephiles. That said, Herzog is one of the true iconoclasts among famous directors working today, and therefore a perfect choice for the award. But it's worth noting that his filmography is laden with at least as many great documentaries as fiction films, even if he famously likes to downplay the difference between these two categories, and did so again when interviewed before the screening, claiming "It's all movies for me." With his documentary, short film and television credentials, Herzog could instead have snugly received the festival's Persistance of Vision Award, which annually honors the career of a filmmaker for working outside the "feature film" sphere. The actual recipient of the award this year was Guy Maddin, another figure whose work fits both inside and outside that sphere. His most widely-seen film is almost certainly the Saddest Music in the World starring Isabella Rossellini but he also has made films for television (Dracula: Pages From a Virgin's Diary) and a good deal of short films, several of which were interspersed with a live interview between Maddin and Steve Seid of the Pacific Film Archive.

The interview demonstrated Maddin to be an incredibly funny and down-to-earth guy, the complete opposite from the über-pretentious aesthete you might think would be the type to name one of his films Odilon Redon or the Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity. I was thrilled to see Maddin's newest film, My Dad is 100 Years Old and doubly thrilled to finally see The Heart of the World, which I had so ruefully missed when it played the 2001 SFIFF, projected onto the Kabuki Theatre's grandest screen (I certainly hope House 1 is not seriously overhauled in the remodel being undertaken by the theatre's new owner.) The Heart of the World equals the visual and narrative complexity of all but the most Byzantinely-plotted feature films, but it packs all its images into the space of six minutes, which is why it just might be the most entertainingly rewatchable short film ever. Well, at least since Tex Avery. It helps that, like Artur Pelechian's equally exhilarating The Beginning and the introduction to Soviet television's news program, Maddin's film is driven by Georgy Sviridov's pulsating and instantly memorable music from the 1965 Mosfilm release Time, Forward! Part of me would have liked to hear Maddin talk more about making The Heart of the World and other shorts (the same part of me that wished the Maddin essay in the festival program didn't focus so much on feature films, considering the POV Award is supposedly for everything but), though my more practical side was too giddy over the subjects he did talk about (like this, for example) to care at all.

The interview demonstrated Maddin to be an incredibly funny and down-to-earth guy, the complete opposite from the über-pretentious aesthete you might think would be the type to name one of his films Odilon Redon or the Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity. I was thrilled to see Maddin's newest film, My Dad is 100 Years Old and doubly thrilled to finally see The Heart of the World, which I had so ruefully missed when it played the 2001 SFIFF, projected onto the Kabuki Theatre's grandest screen (I certainly hope House 1 is not seriously overhauled in the remodel being undertaken by the theatre's new owner.) The Heart of the World equals the visual and narrative complexity of all but the most Byzantinely-plotted feature films, but it packs all its images into the space of six minutes, which is why it just might be the most entertainingly rewatchable short film ever. Well, at least since Tex Avery. It helps that, like Artur Pelechian's equally exhilarating The Beginning and the introduction to Soviet television's news program, Maddin's film is driven by Georgy Sviridov's pulsating and instantly memorable music from the 1965 Mosfilm release Time, Forward! Part of me would have liked to hear Maddin talk more about making The Heart of the World and other shorts (the same part of me that wished the Maddin essay in the festival program didn't focus so much on feature films, considering the POV Award is supposedly for everything but), though my more practical side was too giddy over the subjects he did talk about (like this, for example) to care at all.I do feel a bit like I'm needlessly nitpicking by trying to demonstrate that Herzog and Maddin could easily have switched awards, if not for the fact that Herzog has the greater and wider reputation. I just think it's worth pointing out that in the past few years the festival has really had two awards for directors: one for big-names and one for lesser-knowns who, like most filmmakers, happen to have some shorts, documentaries, animation, and/or TV work under their belts. I don't mind as long as both choices are good ones; "it's all movies for me." And this year was nothing like 2002, where it was clear to any discerning cinephile that the director of greater stature if not international fame (Fernando Birri) was receiving the "less prestigious" award while a director of three and a half films (not to disparage the quality of Bulworth, which I really like) got the bigger-billed one. I've long since wondered if it was more than coincidence that it was after that year that the Kurosawa estate wanted the name of the award back.

I missed the big events for Peter J. Owens Award recipient Ed Harris and Kanbar Award recipient Jean-Claude Carrière, the latter especially to my great regret. But the festival made what I thought were very appropriate selections of screenings to accompany the q-and-a sessions: a Flash of Green for Harris and Belle De Jour for Carrière. A Flash of Green is one of two films I've seen by Floridian director Victor Nunez, and like Ulee's Gold, which helped Peter Fonda grab a Golden Globe award, it's a showcase for a lead actor, in this case Harris, to construct a character of uncommon richness for a two-hour movie. As such it's a good choice to accompany presentation of an acting award, even if as a film it isn't quite as tightly-structured as Ulee's Gold is. And though I've seen too small a sample of Jean-Claude Carrière's career to feel confident in calling Belle De Jour his crowning achievement (rivaled in my mind only by the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), it is a self-reflexive masterpiece of cinematic illogic. It's also the only Carrière-Buñuel collaboration withheld from a brief series that played the Castro during the last few months of Anita Monga's stewardship of that theatre in 2004, and was therefore was ripe for a Frisco theatrical viewing.

I missed the big events for Peter J. Owens Award recipient Ed Harris and Kanbar Award recipient Jean-Claude Carrière, the latter especially to my great regret. But the festival made what I thought were very appropriate selections of screenings to accompany the q-and-a sessions: a Flash of Green for Harris and Belle De Jour for Carrière. A Flash of Green is one of two films I've seen by Floridian director Victor Nunez, and like Ulee's Gold, which helped Peter Fonda grab a Golden Globe award, it's a showcase for a lead actor, in this case Harris, to construct a character of uncommon richness for a two-hour movie. As such it's a good choice to accompany presentation of an acting award, even if as a film it isn't quite as tightly-structured as Ulee's Gold is. And though I've seen too small a sample of Jean-Claude Carrière's career to feel confident in calling Belle De Jour his crowning achievement (rivaled in my mind only by the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), it is a self-reflexive masterpiece of cinematic illogic. It's also the only Carrière-Buñuel collaboration withheld from a brief series that played the Castro during the last few months of Anita Monga's stewardship of that theatre in 2004, and was therefore was ripe for a Frisco theatrical viewing.The Mel Novikoff Award "for enhancing the public's awareness and enjoyment of film" that Monga recieved at the 2005 edition of the festival was not given out at this year's edition. I thought this was a bit of a shame, not only because I support the spirit of an award given to film programmers, preservationists, critics, and other people in the film community besides the filmmakers awarded by so many other groups, but also for the purely selfish reason that the award has traditionally provided an opportunity to see some of the most intriguing and hard-to-find films the festival has screened in the past few years. The collection of silent shorts Paolo Cherchi Usai picked out in 2004 (which I caught, and which turned me into a Charley Bowers fan), or the mini-retro for Jacques Rozier brought by Cahiers du Cinéma when it was awarded in 2001 (which I missed, and which hasn't made a return visit to the area) are just a few examples.

Instead, Monga was offered a carte blanche programming selection by the SFIFF. She decided to bring a print of Hal Roach's 1940 gender-bender comedy Turnabout, a glimpse of the UCLA Film and Television Archive's biennial festival of preservation happening in Los Angeles this July and August. This festival sounds well worth a road trip, especially since I unfortunately missed both screenings of Turnabout, one due to my work schedule and the other because I felt compelled to see the Alloy Orchestra's second-ever public performance of a newly-composed score to the 1925 Rudolph Valentino vehicle, The Eagle. Directed by Clarence Brown (one of Andrew Sarris's "subjects for further research"), The Eagle rarely seemed better than average on its own merits, but it's the kind of film that really plays to the Alloys' strongest points: propelling the excitement of action sequences and modernizing melodrama that with a more traditional score might seem unbearable to unaccustomed audiences. The group also performed at a matinee screening of three short films: Buster Keaton's One Week, Fatty Arbuckle's Back Stage, and Jane Gillooly's modern silent Dragonflies, the Baby Cries.

A totally different kind of pairing of live musicians with an underscreened film classic occurred a few days later when Deerhoof took on Harry Smith's 1962 epic of iconography, Heaven and Earth Magic. The SFIFF has made a tradition of bringing some of this century's best American indie rockers together with some of the last century's most eye-popping films since the cusp of the two centuries in 2000, when Tom Verlaine performed in front of a set of surrealist shorts. I've always appreciated the interpretations the musicians have come up with, sometimes very much so, though the purist in me feels that they're often not the best way for someone to be introduced to the films. This time around I was particularly skeptical because Heaven and Earth Magic is not a silent work; it has a soundtrack of library sound effects put together musique concrète-style. On the other hand I knew that the huge Castro screen would display Smith's visuals better than I could possibly hope to see them again, barring re-discovery of the original color version now lost, and when I finally started paying attention to friends who'd been touting Deerhoof to me for years and listened to some of their albums in anticipation of the event, I grew more optimistic.

A totally different kind of pairing of live musicians with an underscreened film classic occurred a few days later when Deerhoof took on Harry Smith's 1962 epic of iconography, Heaven and Earth Magic. The SFIFF has made a tradition of bringing some of this century's best American indie rockers together with some of the last century's most eye-popping films since the cusp of the two centuries in 2000, when Tom Verlaine performed in front of a set of surrealist shorts. I've always appreciated the interpretations the musicians have come up with, sometimes very much so, though the purist in me feels that they're often not the best way for someone to be introduced to the films. This time around I was particularly skeptical because Heaven and Earth Magic is not a silent work; it has a soundtrack of library sound effects put together musique concrète-style. On the other hand I knew that the huge Castro screen would display Smith's visuals better than I could possibly hope to see them again, barring re-discovery of the original color version now lost, and when I finally started paying attention to friends who'd been touting Deerhoof to me for years and listened to some of their albums in anticipation of the event, I grew more optimistic. I was not disappointed. Deerhoof resisted any temptation they might have had to utilize their ability to rock out and overwhelm Smith's images. Instead they used their instruments, as well as the Castro's Wurlitzer organ that they had to obtain extra-special permission to incorporate, as if they encompassed a gigantic library of sound effects as eerie and off-kilter as the wolf howls and thunder cracks employed by Smith in his original sound track. Sure, they put together a mean rhythm for a section here and a section there, the most memorable being during a scene of whirring gears and orbs toward the end of the film. But they always seemed conscious of the delicate pacing of Smith's animation. When the nourishing meal of Heaven and Earth Magic was finished, the band moved on to provide its fans in the audience with the dessert many of them had been craving: several of Smith's Early Abstractions played on the screen, but instead of the Meet the Beatles! soundtrack long associated with the films, Deerhoof played and sang four songs from its latest album The Runners Four (plus "Flower" from Apple O') and it was a lot of fun. Clearly, the band took care to match each film with the right song. For example, what I think might have been Abstraction No. 4, a film of "black and white abstractions of dots and grillworks" was accompanied by the song "Spy On You", which lent an air of paranoia to the the searching and probing motion of light that makes up the film. I enjoyed these added meanings introduced by the Deerhoof lyrics, though I also am mindful of what Jonas Mekas in his Movie Journal has to say regarding audience reaction to the soundtrack that, as legend has it, he was the one to add to Smith's films:

I was not disappointed. Deerhoof resisted any temptation they might have had to utilize their ability to rock out and overwhelm Smith's images. Instead they used their instruments, as well as the Castro's Wurlitzer organ that they had to obtain extra-special permission to incorporate, as if they encompassed a gigantic library of sound effects as eerie and off-kilter as the wolf howls and thunder cracks employed by Smith in his original sound track. Sure, they put together a mean rhythm for a section here and a section there, the most memorable being during a scene of whirring gears and orbs toward the end of the film. But they always seemed conscious of the delicate pacing of Smith's animation. When the nourishing meal of Heaven and Earth Magic was finished, the band moved on to provide its fans in the audience with the dessert many of them had been craving: several of Smith's Early Abstractions played on the screen, but instead of the Meet the Beatles! soundtrack long associated with the films, Deerhoof played and sang four songs from its latest album The Runners Four (plus "Flower" from Apple O') and it was a lot of fun. Clearly, the band took care to match each film with the right song. For example, what I think might have been Abstraction No. 4, a film of "black and white abstractions of dots and grillworks" was accompanied by the song "Spy On You", which lent an air of paranoia to the the searching and probing motion of light that makes up the film. I enjoyed these added meanings introduced by the Deerhoof lyrics, though I also am mindful of what Jonas Mekas in his Movie Journal has to say regarding audience reaction to the soundtrack that, as legend has it, he was the one to add to Smith's films: What this is, it's again the dear, dear ego, not being able to give yourself to anything on that screen unless it's you there on that silver screen, with all the Beatles songs you like so much and everything else you know so well. But to go into unknown territory...and through all that silence...uh, that can be dangerous.

Though I'm hopeful that the SFIFF will decide for next year's historic 50th anniversary to reverse the trend of decreasing revival selections, I'm also thankful that I got to see what I did this year. But truly, my appetite to rediscover classic films amidst the hubbub of a festival setting has only barely been staved off. Which is why I'm so excited about returning to the Castro for the next Silent Film Festival. The schedule has just been fully announced. For a director-centric film lover like me, this 11th year of the festival looks like it might be the best yet. It includes the first Silent Film Fest appearances by great auteurs from John Ford (the 1917 Western Bucking Broadway, introduced by Ford biographer Joseph McBride and Ford actor Harry Carey, Jr. July 15) to G.W. Pabst (a new Louise Brooks centenary print of Pandora's Box, July 15) to Boris Barnet (The Girl With The Hatbox starring the gorgeous half-Ukranian, half-Swedish actress Anna Sten, July 16) to Leo McCarey (three of his Laurel and Hardy two-reelers play July 16.) Frenchman Julien Duvivier's reputation has still yet to bounce back from the hit taken when the nouvelle vague lumped him in with the Tradition-of-Quality filmmakers they liked to sneer at; might Au Bonheur Des Dames (July 15) help kickstart renewed interest in the director? And though I already knew four of the titles selected for the festival, I'm freshly excited about them all over again now that I've learned who's been entrusted with the musical accompaniment: Clark Wilson on organ for the July 14 opening night film Seventh Heaven, Michael Mortilla on piano for the July 15 Sparrows, Jon Mirsalis on piano for July 16th's The Unholy Three, and last but most assuredly not least Dennis James at the organ for the closing film Show People July16.

Though I'm hopeful that the SFIFF will decide for next year's historic 50th anniversary to reverse the trend of decreasing revival selections, I'm also thankful that I got to see what I did this year. But truly, my appetite to rediscover classic films amidst the hubbub of a festival setting has only barely been staved off. Which is why I'm so excited about returning to the Castro for the next Silent Film Festival. The schedule has just been fully announced. For a director-centric film lover like me, this 11th year of the festival looks like it might be the best yet. It includes the first Silent Film Fest appearances by great auteurs from John Ford (the 1917 Western Bucking Broadway, introduced by Ford biographer Joseph McBride and Ford actor Harry Carey, Jr. July 15) to G.W. Pabst (a new Louise Brooks centenary print of Pandora's Box, July 15) to Boris Barnet (The Girl With The Hatbox starring the gorgeous half-Ukranian, half-Swedish actress Anna Sten, July 16) to Leo McCarey (three of his Laurel and Hardy two-reelers play July 16.) Frenchman Julien Duvivier's reputation has still yet to bounce back from the hit taken when the nouvelle vague lumped him in with the Tradition-of-Quality filmmakers they liked to sneer at; might Au Bonheur Des Dames (July 15) help kickstart renewed interest in the director? And though I already knew four of the titles selected for the festival, I'm freshly excited about them all over again now that I've learned who's been entrusted with the musical accompaniment: Clark Wilson on organ for the July 14 opening night film Seventh Heaven, Michael Mortilla on piano for the July 15 Sparrows, Jon Mirsalis on piano for July 16th's The Unholy Three, and last but most assuredly not least Dennis James at the organ for the closing film Show People July16.I also found out the schedule for the Bronco Billy silent film festival happening a few weekends beforehand, June 23-25 at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum across the bay in Fremont. Programs devoted to Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin and Harold Lloyd jumped out on a brief initial glance.

Sunday, May 7

Summer on Frisco Bay

I hope to sum up my experiences at the 49th SFIFF in the next few days, but before I do I'd like to do a little summer preview as is customary during the season. You may have thought it was still mid-spring, but in the movie industry summer has officially launched now that there's a gigantic Tom Cruise threequel hogging screens across the country. Luckily there are a few left in Frisco for showing more adventurous fare. In fact, in the face of all the oxygen that gets sucked up by the weekly tentpole releases appearing at multiplexes in the coming months, it seems as if some local arthouse bookers feel freed up by the diversion of expectations onto would-be blockbusters to experiment a little more than they have done lately.

Take the freshly-printed calendars for the Shattuck, Lumiere, and Opera Plaza: after many months of focusing mainly on documentaries and Indiewood films, the new batch has a very healthy selection of foreign-language narrative features. Olivier Assayas's Clean, for which Maggie Cheung won the Best Actress award at Cannes 2004, is finally opening May 26, for example. Dominik Moll's Cannes 2005 opener Lemming comes June 23. André Téchiné's Changing Times arrives July 21 and Claude Chabrol's the Bridesmaid finishes off the calendar on August 11th. And it's not just French films either: Cavite from the Philippines, the Death of Mr. Lazarescu from Romania, and the Hidden Blade and Azumi from Japan will begin week-long stints June 16, June 30, July 7 and July 28 respectively. And though it's not on the printed calendar, Eran Riklis's excellent The Syrian Bride will be opening at the Opera Plaza May 12th. Back in the Anglophone domain, one of the SFIFF films I kept hearing good things about, but not in time to rearrange my schedule to see it, was the British mockumentary Brothers of the Head. I'm glad to know I'll have another chance starting August 4th.

Take the freshly-printed calendars for the Shattuck, Lumiere, and Opera Plaza: after many months of focusing mainly on documentaries and Indiewood films, the new batch has a very healthy selection of foreign-language narrative features. Olivier Assayas's Clean, for which Maggie Cheung won the Best Actress award at Cannes 2004, is finally opening May 26, for example. Dominik Moll's Cannes 2005 opener Lemming comes June 23. André Téchiné's Changing Times arrives July 21 and Claude Chabrol's the Bridesmaid finishes off the calendar on August 11th. And it's not just French films either: Cavite from the Philippines, the Death of Mr. Lazarescu from Romania, and the Hidden Blade and Azumi from Japan will begin week-long stints June 16, June 30, July 7 and July 28 respectively. And though it's not on the printed calendar, Eran Riklis's excellent The Syrian Bride will be opening at the Opera Plaza May 12th. Back in the Anglophone domain, one of the SFIFF films I kept hearing good things about, but not in time to rearrange my schedule to see it, was the British mockumentary Brothers of the Head. I'm glad to know I'll have another chance starting August 4th.

The Red Vic's new calendar can be picked up around town now too, though it's not yet available online. The first half focuses on last-chance theatrical screenings of recent releases you may have blinked and missed, like four films that played the SFIFF last year and had short runs in theatres subsequently: Following Sean (now playing through May 8), the Boys of Baraka (May 14-15), Duck Season (May 21-22) and the Real Dirt on Farmer John (June 4-7). And then there are films that had slightly longer runs but are worth catching at least once more before the prints disappear into the vault, most notably Caché (May 16-17), the New World (May 18-20) and I Am a Sex Addict (June 23-27), though the latter is digitally distributed so there's no physical print to be vaulted. The other side of the calendar features the only Red Vic premiere this time around, July 12-15th's Rise Above: the Tribe 8 Documentary, but it also contains some healthy repertory selections. If you missed the currently-circulating the Conformist at the Castro and the Balboa (For some reason, possibly connected to the closing of the Act 1 & 2, it didn't play at an East Bay Landmark last week as scheduled after all), it comes to the Red Vic July 16-17. Though as far as I know the theatre isn't equipped with a polarized screen, perhaps by mid-July a license to sell beer and wine will be in place as hoped, which will more than make up for slightly technically inferior 3-D projection of Creature From the Black Lagoon July 20-22 and It Came From Outer Space July 27-29. And it seems like every time Hiroshi Teshigahara's meditative documentary Antonio Gaudi comes to Haight Street it earns a longer run; this one lasts August 6-10.

I mentioned the Castro and the Balboa; they both have exciting new calendars available now too. The Balboa's, which has been available in hard copy for a little while, is now online too. Currently they're playing the Bollywood hit Rang de Basanti, and the fascinating-sounding Yang Bang Xi: the 8 Model Works arrives Friday. They also host a Jazz/Noir Film Festival May 19-21 to get you back in the mood for the Film Noir Foundation's rescheduled Charlie Haden Quartet West concert May 27 at the Herbst. But I'm most eagerly anticipating the Boris Karloff series that runs from his pre-Frankenstein days through his Val Lewton stint (represented by the Body Snatcher June 6) to his 1960's work with cult-film directors like Mario Bava and Roger Corman and finally Peter Bogdanovich's directorial debut Targets (June 16). I'm particularly excited to see the original Scarface on the big screen on June 6, Edgar G. Ulmer's elegantly bizarre the Black Cat on June 21, and a John Ford film I've never caught, the Lost Patrol (June 7). There's even a pair of films not starring Karloff but absolutely connected to his pivotal role in the Frankenstein mythology: Spanish auteur Victor Erice's the Sprit of the Beehive June 9-15 and Bill Condon's Gods and Monsters June 16.

I mentioned the Castro and the Balboa; they both have exciting new calendars available now too. The Balboa's, which has been available in hard copy for a little while, is now online too. Currently they're playing the Bollywood hit Rang de Basanti, and the fascinating-sounding Yang Bang Xi: the 8 Model Works arrives Friday. They also host a Jazz/Noir Film Festival May 19-21 to get you back in the mood for the Film Noir Foundation's rescheduled Charlie Haden Quartet West concert May 27 at the Herbst. But I'm most eagerly anticipating the Boris Karloff series that runs from his pre-Frankenstein days through his Val Lewton stint (represented by the Body Snatcher June 6) to his 1960's work with cult-film directors like Mario Bava and Roger Corman and finally Peter Bogdanovich's directorial debut Targets (June 16). I'm particularly excited to see the original Scarface on the big screen on June 6, Edgar G. Ulmer's elegantly bizarre the Black Cat on June 21, and a John Ford film I've never caught, the Lost Patrol (June 7). There's even a pair of films not starring Karloff but absolutely connected to his pivotal role in the Frankenstein mythology: Spanish auteur Victor Erice's the Sprit of the Beehive June 9-15 and Bill Condon's Gods and Monsters June 16.

The Castro's new calendar wasn't ready to hand out at the SFIFF closing film Thursday night, but it's available online now. It starts May 12 with a 5-film Jacques Demy series, then a pair of Liza Minelli double features (perhaps to go along with her dad's series still chugging along at the Stanford.) May 25th will bring a Jane Russell double-bill of Hot Blood (by Nick Ray) and Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (not by Howard Hawks). On June 1 F.W. Murnau's Faust will screen, followed by a week of Raiders of the Lost Ark and on June 9 another MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS triple-bill (this time actually a Latch-Key Kids quadruple-bill, as it begins with the rare 16mm short Cipher in the Snow before collecting fans of Rumble Fish, the Warriors and Streets of Fire under one roof.) Before you know it, it's June 15, the opening night of Frameline's 30th annual festival. Opening with Puccini For Beginners and closing June 25 with the Spanish film Queens, most of the rest of the so-far announced films have been off my radar screen, except for François Ozon's latest Time to Leave June 20 (and his 8 Women which is getting a Monday matinee reprise June 19) and Backstage (also June 20), which I hope I'm not wrong in assuming is the same film that just played at Tribeca and the SFIFF to strong acclaim. I was sorry to have missed it.

Frameline is teasing fans with only a hint of its schedule for now, but it also will be spreading the festival to four venues outside the Castro district: the Victoria, the Empire (smart choice; it's just a quick MUNI trip under Twin Peaks to the Castro), the Roxie and, in Oakland, the Parkway. The latter has a full plate of special events coming up too, everything from Lucio Fulci's the Beyond May 25 to Euzhan Palcy's Sugar Cane Alley July 2 to the Big Lebowski May 18. The Roxie, meanwhile, is currently in the midst of a Psychology-themed series and is gearing up for the DocFest running Friday, May 12 until May 21 (also at the Women's Building), and beginning June 9 the third Another Hole in the Head festival, to include Shinya Tsukamoto's Haze and a revival of Walerian Borowczyk's the Beast. The Roxie will also have a week of Jeff Adachi's the Slanted Screen starting May 19.

In the North Bay, the Rafael Film Center joins the Balboa in playing Spirit of the Beehive June 9th, plays the SFIFF Audience Award winner Look Both Ways starting June 17th, and runs a motorcycle film series throughout June. The Lark is hosting a May 31 appearance of Claude Jarman and screening of the film he won an Oscar for sixty years ago: the Yearling. And if you ever wanted to check out Copia in Napa, June 23rd seems like a good time, as Les Blank will be there to screen his Burden of Dreams.

In the North Bay, the Rafael Film Center joins the Balboa in playing Spirit of the Beehive June 9th, plays the SFIFF Audience Award winner Look Both Ways starting June 17th, and runs a motorcycle film series throughout June. The Lark is hosting a May 31 appearance of Claude Jarman and screening of the film he won an Oscar for sixty years ago: the Yearling. And if you ever wanted to check out Copia in Napa, June 23rd seems like a good time, as Les Blank will be there to screen his Burden of Dreams.

I could go on and on with this. Artists' Television Access has a bunch of interesting programs on the docket. The Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum has its May schedule in place, and it's quite enticing: D.W. Griffith's Hearts of the World on the 13th, Harold Lloyd is a Sailor-Made Man on the 20th, and Allan Dwan's Manhattan Madness on the 27th. The Yerba Buena Center for the Arts has its screenings set through June; they include the Perfumed Nightmare May 21, the fascinating and ironic Al'leessi...An African Actress June 14, and a selection of films made by Edinburgh Castle Film Night regulars (disclosure: many of them are my friends) June 25. I have confidence that these films will hold up to the scrutiny of a non-inebriated audience, though I'll be curious to hear how this afternoon's similarly ECFN-infected screenings at the PFA go. I notice the Berkeley venue has given itself several weeks to clean up after the event before it reopens May 25 with the Weeping Meadow.

Have I left anything particularly interesting out?

Take the freshly-printed calendars for the Shattuck, Lumiere, and Opera Plaza: after many months of focusing mainly on documentaries and Indiewood films, the new batch has a very healthy selection of foreign-language narrative features. Olivier Assayas's Clean, for which Maggie Cheung won the Best Actress award at Cannes 2004, is finally opening May 26, for example. Dominik Moll's Cannes 2005 opener Lemming comes June 23. André Téchiné's Changing Times arrives July 21 and Claude Chabrol's the Bridesmaid finishes off the calendar on August 11th. And it's not just French films either: Cavite from the Philippines, the Death of Mr. Lazarescu from Romania, and the Hidden Blade and Azumi from Japan will begin week-long stints June 16, June 30, July 7 and July 28 respectively. And though it's not on the printed calendar, Eran Riklis's excellent The Syrian Bride will be opening at the Opera Plaza May 12th. Back in the Anglophone domain, one of the SFIFF films I kept hearing good things about, but not in time to rearrange my schedule to see it, was the British mockumentary Brothers of the Head. I'm glad to know I'll have another chance starting August 4th.

Take the freshly-printed calendars for the Shattuck, Lumiere, and Opera Plaza: after many months of focusing mainly on documentaries and Indiewood films, the new batch has a very healthy selection of foreign-language narrative features. Olivier Assayas's Clean, for which Maggie Cheung won the Best Actress award at Cannes 2004, is finally opening May 26, for example. Dominik Moll's Cannes 2005 opener Lemming comes June 23. André Téchiné's Changing Times arrives July 21 and Claude Chabrol's the Bridesmaid finishes off the calendar on August 11th. And it's not just French films either: Cavite from the Philippines, the Death of Mr. Lazarescu from Romania, and the Hidden Blade and Azumi from Japan will begin week-long stints June 16, June 30, July 7 and July 28 respectively. And though it's not on the printed calendar, Eran Riklis's excellent The Syrian Bride will be opening at the Opera Plaza May 12th. Back in the Anglophone domain, one of the SFIFF films I kept hearing good things about, but not in time to rearrange my schedule to see it, was the British mockumentary Brothers of the Head. I'm glad to know I'll have another chance starting August 4th.The Red Vic's new calendar can be picked up around town now too, though it's not yet available online. The first half focuses on last-chance theatrical screenings of recent releases you may have blinked and missed, like four films that played the SFIFF last year and had short runs in theatres subsequently: Following Sean (now playing through May 8), the Boys of Baraka (May 14-15), Duck Season (May 21-22) and the Real Dirt on Farmer John (June 4-7). And then there are films that had slightly longer runs but are worth catching at least once more before the prints disappear into the vault, most notably Caché (May 16-17), the New World (May 18-20) and I Am a Sex Addict (June 23-27), though the latter is digitally distributed so there's no physical print to be vaulted. The other side of the calendar features the only Red Vic premiere this time around, July 12-15th's Rise Above: the Tribe 8 Documentary, but it also contains some healthy repertory selections. If you missed the currently-circulating the Conformist at the Castro and the Balboa (For some reason, possibly connected to the closing of the Act 1 & 2, it didn't play at an East Bay Landmark last week as scheduled after all), it comes to the Red Vic July 16-17. Though as far as I know the theatre isn't equipped with a polarized screen, perhaps by mid-July a license to sell beer and wine will be in place as hoped, which will more than make up for slightly technically inferior 3-D projection of Creature From the Black Lagoon July 20-22 and It Came From Outer Space July 27-29. And it seems like every time Hiroshi Teshigahara's meditative documentary Antonio Gaudi comes to Haight Street it earns a longer run; this one lasts August 6-10.

I mentioned the Castro and the Balboa; they both have exciting new calendars available now too. The Balboa's, which has been available in hard copy for a little while, is now online too. Currently they're playing the Bollywood hit Rang de Basanti, and the fascinating-sounding Yang Bang Xi: the 8 Model Works arrives Friday. They also host a Jazz/Noir Film Festival May 19-21 to get you back in the mood for the Film Noir Foundation's rescheduled Charlie Haden Quartet West concert May 27 at the Herbst. But I'm most eagerly anticipating the Boris Karloff series that runs from his pre-Frankenstein days through his Val Lewton stint (represented by the Body Snatcher June 6) to his 1960's work with cult-film directors like Mario Bava and Roger Corman and finally Peter Bogdanovich's directorial debut Targets (June 16). I'm particularly excited to see the original Scarface on the big screen on June 6, Edgar G. Ulmer's elegantly bizarre the Black Cat on June 21, and a John Ford film I've never caught, the Lost Patrol (June 7). There's even a pair of films not starring Karloff but absolutely connected to his pivotal role in the Frankenstein mythology: Spanish auteur Victor Erice's the Sprit of the Beehive June 9-15 and Bill Condon's Gods and Monsters June 16.

I mentioned the Castro and the Balboa; they both have exciting new calendars available now too. The Balboa's, which has been available in hard copy for a little while, is now online too. Currently they're playing the Bollywood hit Rang de Basanti, and the fascinating-sounding Yang Bang Xi: the 8 Model Works arrives Friday. They also host a Jazz/Noir Film Festival May 19-21 to get you back in the mood for the Film Noir Foundation's rescheduled Charlie Haden Quartet West concert May 27 at the Herbst. But I'm most eagerly anticipating the Boris Karloff series that runs from his pre-Frankenstein days through his Val Lewton stint (represented by the Body Snatcher June 6) to his 1960's work with cult-film directors like Mario Bava and Roger Corman and finally Peter Bogdanovich's directorial debut Targets (June 16). I'm particularly excited to see the original Scarface on the big screen on June 6, Edgar G. Ulmer's elegantly bizarre the Black Cat on June 21, and a John Ford film I've never caught, the Lost Patrol (June 7). There's even a pair of films not starring Karloff but absolutely connected to his pivotal role in the Frankenstein mythology: Spanish auteur Victor Erice's the Sprit of the Beehive June 9-15 and Bill Condon's Gods and Monsters June 16.The Castro's new calendar wasn't ready to hand out at the SFIFF closing film Thursday night, but it's available online now. It starts May 12 with a 5-film Jacques Demy series, then a pair of Liza Minelli double features (perhaps to go along with her dad's series still chugging along at the Stanford.) May 25th will bring a Jane Russell double-bill of Hot Blood (by Nick Ray) and Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (not by Howard Hawks). On June 1 F.W. Murnau's Faust will screen, followed by a week of Raiders of the Lost Ark and on June 9 another MiDNiTES FOR MANiACS triple-bill (this time actually a Latch-Key Kids quadruple-bill, as it begins with the rare 16mm short Cipher in the Snow before collecting fans of Rumble Fish, the Warriors and Streets of Fire under one roof.) Before you know it, it's June 15, the opening night of Frameline's 30th annual festival. Opening with Puccini For Beginners and closing June 25 with the Spanish film Queens, most of the rest of the so-far announced films have been off my radar screen, except for François Ozon's latest Time to Leave June 20 (and his 8 Women which is getting a Monday matinee reprise June 19) and Backstage (also June 20), which I hope I'm not wrong in assuming is the same film that just played at Tribeca and the SFIFF to strong acclaim. I was sorry to have missed it.

Frameline is teasing fans with only a hint of its schedule for now, but it also will be spreading the festival to four venues outside the Castro district: the Victoria, the Empire (smart choice; it's just a quick MUNI trip under Twin Peaks to the Castro), the Roxie and, in Oakland, the Parkway. The latter has a full plate of special events coming up too, everything from Lucio Fulci's the Beyond May 25 to Euzhan Palcy's Sugar Cane Alley July 2 to the Big Lebowski May 18. The Roxie, meanwhile, is currently in the midst of a Psychology-themed series and is gearing up for the DocFest running Friday, May 12 until May 21 (also at the Women's Building), and beginning June 9 the third Another Hole in the Head festival, to include Shinya Tsukamoto's Haze and a revival of Walerian Borowczyk's the Beast. The Roxie will also have a week of Jeff Adachi's the Slanted Screen starting May 19.

In the North Bay, the Rafael Film Center joins the Balboa in playing Spirit of the Beehive June 9th, plays the SFIFF Audience Award winner Look Both Ways starting June 17th, and runs a motorcycle film series throughout June. The Lark is hosting a May 31 appearance of Claude Jarman and screening of the film he won an Oscar for sixty years ago: the Yearling. And if you ever wanted to check out Copia in Napa, June 23rd seems like a good time, as Les Blank will be there to screen his Burden of Dreams.

In the North Bay, the Rafael Film Center joins the Balboa in playing Spirit of the Beehive June 9th, plays the SFIFF Audience Award winner Look Both Ways starting June 17th, and runs a motorcycle film series throughout June. The Lark is hosting a May 31 appearance of Claude Jarman and screening of the film he won an Oscar for sixty years ago: the Yearling. And if you ever wanted to check out Copia in Napa, June 23rd seems like a good time, as Les Blank will be there to screen his Burden of Dreams.I could go on and on with this. Artists' Television Access has a bunch of interesting programs on the docket. The Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum has its May schedule in place, and it's quite enticing: D.W. Griffith's Hearts of the World on the 13th, Harold Lloyd is a Sailor-Made Man on the 20th, and Allan Dwan's Manhattan Madness on the 27th. The Yerba Buena Center for the Arts has its screenings set through June; they include the Perfumed Nightmare May 21, the fascinating and ironic Al'leessi...An African Actress June 14, and a selection of films made by Edinburgh Castle Film Night regulars (disclosure: many of them are my friends) June 25. I have confidence that these films will hold up to the scrutiny of a non-inebriated audience, though I'll be curious to hear how this afternoon's similarly ECFN-infected screenings at the PFA go. I notice the Berkeley venue has given itself several weeks to clean up after the event before it reopens May 25 with the Weeping Meadow.

Have I left anything particularly interesting out?

Thursday, May 4

Festival award-winners

The SFIFF announced its awards at an event last night that I didn't attend (I was in Berkeley being hypnotized by staring into Aleksander Sokurov's the Sun), but I've learned the winners elsewhere. As usual, the great majority of the awarded films are among the ones I didn't see. The SKYY Prize for the best first feature was given to Taking Father Home by Ying Liang. The FIPRESCI jury prize went to another first feature, Ryan Fleck's Half Nelson. Among the Golden Gate Award (GGA) winners I failed to fit into my schedule, the Documentary Feature winner was Michael Glawogger's Workingman's Death (pictured), which opens for a week at the Roxie starting tomorrow. Glawogger previously won a GGA in 1999 for Megacities. In a "spread the wealth" maneuver, Sam Green's lot 63 grave 3 won the Documentary Short award and Karina Epperlein's Phoenix Dance won the Bay Area Documentary Short award, as both films were eligible in both categories. (The prize money and Kodak gift certificate is the same for each of the two winners.) The winning Narrative Short was Sebastian Alfie's Love at 4 PM and the Bay Area Non-Documentary Short was Natalija Vekic's Lost & Found. The Award to a Work For Kids and Families went to Sirah, by Cristine Spindler. The Works for Television Awards were previously known and were shown on a pair of festival programs: Seeds of Doubt with Bing Can Sing, and They Chose China with Thornton Dial.

The SFIFF announced its awards at an event last night that I didn't attend (I was in Berkeley being hypnotized by staring into Aleksander Sokurov's the Sun), but I've learned the winners elsewhere. As usual, the great majority of the awarded films are among the ones I didn't see. The SKYY Prize for the best first feature was given to Taking Father Home by Ying Liang. The FIPRESCI jury prize went to another first feature, Ryan Fleck's Half Nelson. Among the Golden Gate Award (GGA) winners I failed to fit into my schedule, the Documentary Feature winner was Michael Glawogger's Workingman's Death (pictured), which opens for a week at the Roxie starting tomorrow. Glawogger previously won a GGA in 1999 for Megacities. In a "spread the wealth" maneuver, Sam Green's lot 63 grave 3 won the Documentary Short award and Karina Epperlein's Phoenix Dance won the Bay Area Documentary Short award, as both films were eligible in both categories. (The prize money and Kodak gift certificate is the same for each of the two winners.) The winning Narrative Short was Sebastian Alfie's Love at 4 PM and the Bay Area Non-Documentary Short was Natalija Vekic's Lost & Found. The Award to a Work For Kids and Families went to Sirah, by Cristine Spindler. The Works for Television Awards were previously known and were shown on a pair of festival programs: Seeds of Doubt with Bing Can Sing, and They Chose China with Thornton Dial. I did see the winner of the GGA Youth Work prize, Karen Lum's Slip of the Tongue (pictured) because it was available in full as part of the International Remix web mash-up project. The clips and remixes are all still up there and anyone can make a new one, though I'm not sure how long that will last after the festival officially ends tonight. This was an innovative and fun way to increase interactivity with some of the festival's short films, plus one that should be considered short only by Lav Diaz standards, the Filipino filmmaker Raya Martin's 90-minute a Short Film About the Indio Nacional. I spent an hour or two making one that relied heavily on Martin's striking black-and-white images, images I found so mysterious and strong that I was compelled to check out the film in full at its first festival screening. It didn't disappoint, and would be a major contender if I had my own personal award for the most audacious film I saw at this year's festival. Perhaps slightly too audacious, Martin's film provoked more walkouts than even the Wayward Cloud, and his extraordinarily long takes and encouragement of extremely unprofessional acting styles tested the limits of even this Apichatpong Weerasethakul fan. I mention Apichatpong because a Short Film About the Indio Nacional reminded me of his films more than any other's, and with encouragement and development I see potential for the young Martin to have a similar career path. By making a film so often reminiscent of silent actualities, he is already engaging directly the film history of his tropical nation where human memory tends to last much longer than film stock.

I did see the winner of the GGA Youth Work prize, Karen Lum's Slip of the Tongue (pictured) because it was available in full as part of the International Remix web mash-up project. The clips and remixes are all still up there and anyone can make a new one, though I'm not sure how long that will last after the festival officially ends tonight. This was an innovative and fun way to increase interactivity with some of the festival's short films, plus one that should be considered short only by Lav Diaz standards, the Filipino filmmaker Raya Martin's 90-minute a Short Film About the Indio Nacional. I spent an hour or two making one that relied heavily on Martin's striking black-and-white images, images I found so mysterious and strong that I was compelled to check out the film in full at its first festival screening. It didn't disappoint, and would be a major contender if I had my own personal award for the most audacious film I saw at this year's festival. Perhaps slightly too audacious, Martin's film provoked more walkouts than even the Wayward Cloud, and his extraordinarily long takes and encouragement of extremely unprofessional acting styles tested the limits of even this Apichatpong Weerasethakul fan. I mention Apichatpong because a Short Film About the Indio Nacional reminded me of his films more than any other's, and with encouragement and development I see potential for the young Martin to have a similar career path. By making a film so often reminiscent of silent actualities, he is already engaging directly the film history of his tropical nation where human memory tends to last much longer than film stock. But I digress. Back to the actual GGA-winning films I did see. There were two others, the Animated Short At the Quinte Hotel (pictured) by Bruce Alcock, and the New Visions awardee site specific_LAS VEGAS 05 by Olivo Barbieri. The latter doesn't quite match up to the two previous year's winners in the New Visions category, Phantom Foreign Vienna and Papillon d'amour, or even to Barbieri's other film in the festival, the non-nominated site specific_SHANGHAI 04 in my mind, but it's certainly a fascinating thing to watch. And At the Quinte Hotel is a nice marriage of poem to image, worthy of attention, and probably the least likely among its fellow nominees to gain a cult following on the internet or a slot in one of Spike and Mike's Sick and Twisted festivals.

But I digress. Back to the actual GGA-winning films I did see. There were two others, the Animated Short At the Quinte Hotel (pictured) by Bruce Alcock, and the New Visions awardee site specific_LAS VEGAS 05 by Olivo Barbieri. The latter doesn't quite match up to the two previous year's winners in the New Visions category, Phantom Foreign Vienna and Papillon d'amour, or even to Barbieri's other film in the festival, the non-nominated site specific_SHANGHAI 04 in my mind, but it's certainly a fascinating thing to watch. And At the Quinte Hotel is a nice marriage of poem to image, worthy of attention, and probably the least likely among its fellow nominees to gain a cult following on the internet or a slot in one of Spike and Mike's Sick and Twisted festivals.After the festival closes tonight I hope to post more wrap-ups of some of the programs I did and didn't see, but for now I'll tide you over with Tilda Swinton's State of the Cinema address, which is a wonderful read. And of course the festival will continue to live on in Frisco as Workingman's Death and the Jean-Claude Carrière miniseries at the Pacific Film Archive both start tomorrow.

UPDATE 5/5/06: The Audience Awards were announced last night just after the screening of a Prairie Home Companion and before the wonderful q-and-a session with Virginia Madsen and Lily Tomlin. The winners were, once again, films I missed at the festival: the the narrative film Look Both Ways, and the documentary Encounter Point barely edging out the honorably-mentioned Who Killed the Electric Car? And for some reason I forgot to list among the GGA winners the Bay Area Documentary Feature winner, Jonestown: The Life and Death of People's Temple by Stanley Nelson. Most of these are expected to be released commericially in Frisco theatres at some point (as is Art School Confidential, though not until next weekend, contradictory to what I wrote in the first edition of this post.)